Fajr, Clocks and Community Routines: How a Mid‑Ramadan Time Shift Will Ripple Through Daily Life

This year’s Ramadan overlaps with the start of Daylight Saving Time, meaning fajr and pre‑dawn meal schedules, evening prayers and family iftars will move an hour later overnight for many North American Muslims. Millions of American Muslims are already adjusting routines — from gym plans to sleep and meal timing — because the clock change falls about halfway through the month.

Fajr timing shifts first for daily routines and community life

Here’s the part that matters: the fast itself doesn’t lengthen by astronomical measure, but the clock‑linked rhythm that organizes worship, work and family time jumps. That sudden shift pushes fajr (the pre‑dawn window tied to waking for the pre‑dawn meal) and sunset‑linked iftar later on the clock, disrupting sleep cycles, commutes and tightly scheduled communal prayers.

- Individuals planning suhoor and sleep patterns must reconfigure waking times almost immediately.

- Workers, students and families who built daily plans around existing clock times will find evening and morning obligations shifted an hour later.

- Communities that coordinate shared iftars, prayer halls and volunteer schedules will need rapid rescheduling for the second half of the month.

What's easy to miss is that while daylight itself follows the sun, our social systems run on clock time; when clocks jump, so does the social organization of worship and rest.

How the clock change plays out: dates, local examples and who is affected

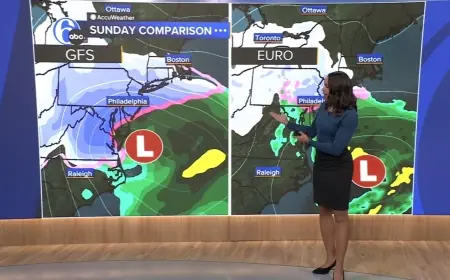

Ramadan starts around Feb. 17 and continues into mid‑March this year. Daylight Saving Time takes effect on March 8, placing that change roughly halfway through the month. Before the clocks move, example evening times climb slowly each day; after the switch, those same sunset events fall an hour later on the clock.

Practical examples drawn from communities this season illustrate the shift in plain terms: a city that was breaking fast around 5: 45 p. m. in the first half of the month could see that clock time jump to about 6: 55 p. m. immediately after the switch. In one Midwestern metropolitan area, early Ramadan days showed pre‑dawn and sunset times near 6: 06 a. m. and 6: 12 p. m.; after the clock change those times were near 6: 42 a. m. and 7: 31 p. m., increasing the clock‑measured fasting window.

The mid‑Ramadan clock shift affects most of the continental United States and much of Canada. Exceptions include jurisdictions that do not observe Daylight Saving Time: Arizona and Hawaii in the U. S., and parts of Canada such as sections of Saskatchewan, Yukon and some regions of British Columbia and Quebec. Regions that change clocks after Ramadan or that do not use Daylight Saving will not experience this mid‑month disruption.

If you’re wondering why this keeps coming up: the Islamic (lunar) calendar is shorter than the civil solar calendar by about 10 days, so Ramadan drifts through the seasons over a roughly 33‑year cycle. That explains why some years bring summer‑length fasts and others land in cooler months — and why the interaction with Daylight Saving varies year to year.

Practical adjustments are already underway: some observers are temporarily altering gym plans, meal choices and sleep arrangements to accommodate the abrupt schedule change. Community organizers and families are rescheduling shared activities to align with the later clock times for the second half of the month.

The real question now is how quickly workplaces, schools and community centers will adapt schedules for those observing the month; confirmation of broader accommodations would be the clearest signal that institutions are responding to the mid‑Ramadan shift.

Key short takeaways:

- Fajr and iftar clock times move an hour later when Daylight Saving begins mid‑month.

- The change affects daily sleep, meal, work and communal prayer routines across much of the continental U. S. and most of Canada.

- People in areas that do not observe Daylight Saving or whose clock changes happen after Ramadan are unaffected by this particular mid‑month disruption.

The bigger signal here is that calendar mechanics and civil time policies intersect in ways that have real, immediate consequences for communal religious life — and those effects are most visible in places where clocks, not just the sun, govern daily schedules.