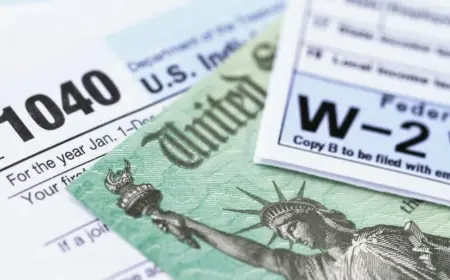

hsbc banker train fare case: Ex-banker banned after dodging £5,900 using 'doughnutting'

Police and rail prosecutors say a former banker has been banned from a commuter railway after admitting a sustained scheme that saved him almost £5, 900 in fares. The case highlights a deliberate pattern of fare evasion known as "doughnutting, " used on services into London between October 2023 and September 2024 (times ET).

How the 'doughnutting' scheme worked

The tactic dubbed "doughnutting" involves buying tickets that cover the outer sections of a commute while leaving the central portion unpaid, effectively creating a hole in the middle of the journey. In this instance, the defendant repeatedly purchased tickets that made it appear he held valid travel for the start and end of trips, while avoiding payment for the middle sections he actually travelled.

Prosecutors told the court the method relied on exploiting gaps in ticket checks and the routine operation of barrier systems. They outlined how false details were used to obtain discounted smartcards and how the tickets were presented to get through automated gates and occasional inspections without triggering further checks mid-journey.

Court outcome, penalties and compensation

The ex-banker admitted fraud at a central London court and was handed a suspended prison sentence alongside community penalties. The legal order includes unpaid work, an obligation to pay compensation for the lost fares, and additional costs tied to the prosecution. On top of the criminal sanction, the individual faces a one-year ban from using the affected commuter railway network.

Railway operators treat repeated or organised fare evasion as criminal conduct rather than a simple civil matter. Penalty fares and on-the-spot fines are common where intent is unclear, but persistent schemes that produce sizable losses to operators typically result in court proceedings, higher fines, compensation orders and the possibility of a criminal record.

Wider fallout for commuters and operators

The case has prompted renewed attention on enforcement and ticketing integrity on commuter routes. Operators and regulators face the challenge of balancing efficient passenger flow with effective checks that deter deliberate evasion. Automated gates and occasional inspections work for many passengers, but this case exposed how determined individuals can exploit routine patterns.

For legitimate commuters, the financial impact of organised evasion can be indirect: higher operational costs and tighter enforcement can translate into higher fares or more intrusive checks. The outcome in this prosecution underlines that repeated and systematic evasion will attract criminal sanctions, potential bans and financial penalties beyond the simple cost of unpaid travel.

Legal experts note that while a single oversight or fare mistake is often treated lightly, repeated manipulation of ticketing rules and the use of false information to secure discounted travel crosses a line into fraud. Rail companies are likely to increase efforts to validate smartcard applications and to strengthen barrier and inspection procedures to reduce the scope for similar schemes.

The former executive's suspended sentence and railway ban serve as a reminder that fare evasion prosecuted as a pattern of criminal behaviour carries consequences that may include community orders, compensation obligations and a lasting criminal record.