Small investors fear losses as brewdog beer owner explores sale

Brewdog’s announcement that it is evaluating strategic options, including a full sale or a break-up of the business, has alarmed tens of thousands of small investors who backed the company through its Equity for Punks crowdfunding scheme. Critics say the possible deal structure could prioritise a private-equity stakeholder and leave many retail shareholders with little or nothing.

How Equity for Punks helped build a global brewer

Launched as an in-house crowdfunding programme, Equity for Punks attracted roughly 220, 000 people across seven fundraising rounds between 2009 and 2021. The scheme raised about £75m in total and helped fund rapid expansion: the company grew from a small unit in north-east Scotland into an international brand operating multiple breweries and more than 100 bars.

Most contributors invested modest sums, often around £500, receiving ordinary shares plus lifestyle perks such as discounts in bars and web orders, birthday beers, and invites to the company’s famously raucous annual meeting dubbed the "Annual General Mayhem. " For some, the investment was as much about community and events as it was about potential capital gains. Others put in far larger amounts; one investor who now fears losing a £12, 000 stake says he had hoped the business would one day float on the stock market, offering a clear path to liquidity.

Why a sale could leave crowdfunders out of pocket

Underlying the risk is the company’s capital structure. In 2017 a private-equity firm bought a significant stake and received preference-share terms that give it seniority over ordinary shareholders if the business is sold. That means a sale or recapitalisation that values the company at a level insufficient to pay out ordinary-equity holders could produce a windfall for the private-equity backer while leaving the smaller, ordinary-share investors with nothing.

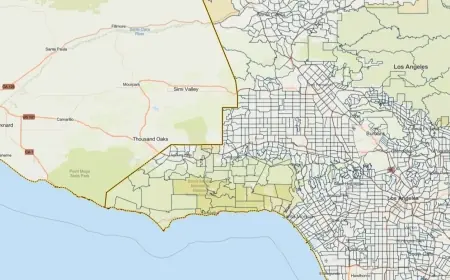

The strategic review now under way is evaluating options from a full company sale to a break-up that could carve the business into parts — for example, separating the bar estate from the brewing operations and brand portfolio. Such a process is commonly used to attract specialist buyers for distinct assets, but it also tends to elevate the claims of holders of preference or secured capital ahead of ordinary shareholders in any proceeds waterfall.

Because Equity for Punks investors were typically issued ordinary shares, they lack the protections that come with preference-stock arrangements. That mismatch between the rights of retail crowdfunders and later institutional investors is at the heart of the current controversy.

Investors’ reactions and what happens next

Responses among crowdfunders range from resignation to anger. Some say they value the social benefits and memories obtained through participation in events and the brewery’s community; others are frustrated that years of loyalty now look likely to deliver no financial return. One long-standing supporter who invested several thousand pounds described feeling misled about the long-term prospects for retail shareholders, while another noted that small investors were left out of meaningful liquidity opportunities when institutional money arrived.

The strategic review will determine whether the business goes to market whole or is sold in parts. For retail investors, the immediate questions are whether a sale can deliver enough value to cover ordinary-share claims and whether any transaction will include measures to protect or compensate the crowdfunding community. Legal and financial outcomes will depend on the terms of any offer and the priorities established by the company’s board and senior stakeholders.

For now, the equity punks’ position serves as a reminder that crowdfunding can carry significant risk: the chance to back a disruptive brand and enjoy perks is not the same as owning liquid, protected equity. Those who invested in hope of a public listing or a profitable exit are now confronting the harsh reality that those outcomes are not guaranteed.