James Van Der Beek’s medical bills and a family fundraiser shine a light on actors’ precarious finances

James Van Der Beek, the actor best known for the title role in Dawson's Creek, died at the age of 48 after a three-year fight with colorectal cancer. In the wake of his death, his wife and six children have turned to a public fundraiser that has raised millions, underscoring how medical expenses can upend the finances of entertainers who were household names in earlier decades.

Fundraiser, donations and memorabilia auctions

Friends set up a fundraiser for Van Der Beek’s family that has drawn wide attention and substantial support. The campaign raised more than $2 million in a short span, with total figures cited around $2. 3 million as the family sought help covering medical and living costs. High-profile individuals and private donors contributed one-off gifts and recurring pledges to help stabilize the household and preserve the children’s education and home.

In the months before his death, Van Der Beek publicly acknowledged how treatment costs had strained the family’s resources. He also turned to selling long-kept career items—memorabilia from roles that defined his rise, including a shirt from the first episode of his breakout series and other keepsakes—to help meet mounting bills. The auctions and the fundraiser together illustrated just how far a family may go to cover care when standard protections fall short.

Career-era contracts, residuals and insurance gaps

Van Der Beek long spoke about the limits of financial protections from his early career. He said he was paid almost nothing under an early contract for the drama that made him a star, and that the deal did not include residuals—ongoing payments when a show is rerun or streamed. Residual income can be a crucial long-term revenue stream for performers, and those written out of such deals can miss decades of payouts that others have used to cover living and medical expenses.

Work since his breakthrough was steady but not necessarily consistent with the thresholds that qualify performers for union-backed benefits. To access health insurance through the actors’ union, performers must meet specific work or earnings minimums: either 108 days of covered work in a year or a minimum earnings threshold on union shoots. It remains unclear whether recent roles met those standards. Van Der Beek continued to work after his diagnosis, appearing in two episodes of a 2025 television project, but that did not eliminate the financial pressure.

Industry shifts and the wider reality faced by many

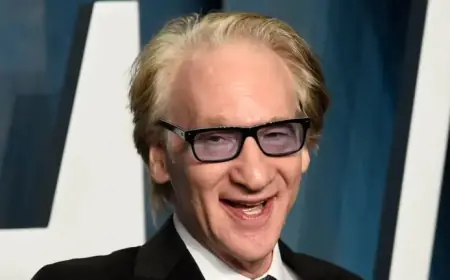

Van Der Beek’s situation is not an isolated example. Changes in how entertainment is made and monetized—most notably the rise of streaming—have disrupted the revenue streams actors traditionally relied upon. One actor who has worked across film and television summed up the change bluntly: "Revenue streams that actors have depended upon have disappeared. " For performers whose most lucrative years predated the streaming era or who signed contracts without robust residual clauses, the result can be financial vulnerability during illness or other crises.

High-profile cases have highlighted gaps in coverage before. Some performers have said they lacked adequate insurance at key moments in their illnesses, and families have launched public appeals when private resources and savings proved insufficient. Van Der Beek’s family fundraiser and the sale of treasured career items have prompted new public conversations about how creative professionals are supported when treatments rack up bills.

As the family mourns, the response to the fundraiser offers one immediate form of support. Longer term, the episode raises questions for an industry grappling with how to ensure that performers—especially those whose fame peaked before current licensing and distribution models—have access to benefits and safety nets when they need them most.