25th Amendment talk around Trump returns as Ed Markey urges action, but the hurdles are as high as the stakes

The 25th Amendment is one of the Constitution’s most powerful emergency valves—and one of its least usable tools in a modern political fight. That tension is exactly why it’s back in the headlines in January 2026. Senator Ed Markey has publicly urged invoking the 25th Amendment against President Donald Trump, pointing to Trump’s recent Greenland push and related communications as evidence of unfitness. The moment matters less because an immediate transfer of power looks likely, and more because it shows how quickly extraordinary constitutional language becomes a public-pressure tactic when ordinary political checks feel stalled.

The uncertainty is baked in: the 25th Amendment can sideline a president, but it requires the president’s own team to start the process—and it demands supermajority votes in Congress if the president fights it.

What the 25th Amendment is—and why Section 4 is the one everyone argues about

The 25th Amendment, ratified in 1967, covers presidential succession and disability. It has four sections, and only one of them is at the center of today’s controversy.

-

Section 1: If the president dies, resigns, or is removed, the vice president becomes president.

-

Section 2: If the vice presidency is vacant, the president nominates a new vice president, and both chambers of Congress must confirm.

-

Section 3: The president can voluntarily transfer power temporarily (often for medical procedures) by declaring an inability in writing; the vice president becomes acting president until the president declares capability again.

-

Section 4: The involuntary route. The vice president and a majority of the cabinet (or another body Congress creates) can declare the president “unable to discharge the powers and duties” of the office. The vice president becomes acting president immediately. If the president contests it, Congress is pulled into the decision.

Section 4 is the lightning rod because it’s not impeachment. It’s a capacity judgment—less about misconduct, more about inability. It’s also the hardest to execute in practice: it asks the vice president and cabinet to move against the president they serve, then survive the political fallout.

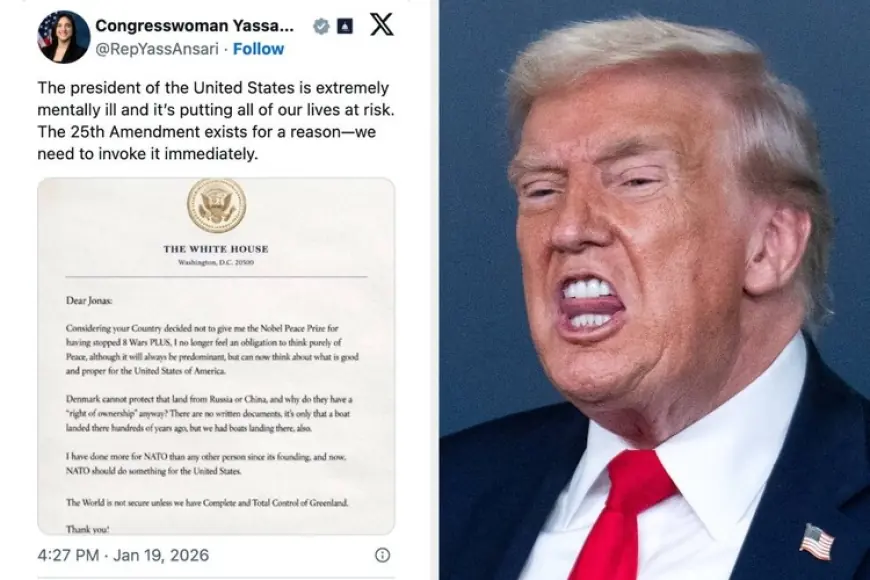

Ed Markey’s call and the Trump context driving the renewed 25th Amendment chatter

Markey’s push lands in the wake of Trump’s escalating Greenland posture—an episode that has drawn intense criticism from Democrats and uneasy reactions across allied capitals. Markey’s argument frames the Greenland effort as part of a pattern of behavior he views as disqualifying, and he has urged the vice president and cabinet to act.

The Greenland dispute itself has become a catalyst because it blends international brinkmanship with unusually personal messaging. Trump’s communications around the issue have tied geopolitical aims to grievances and status claims, turbocharging questions about judgment, restraint, and decision-making.

Other Democrats and public figures have echoed the 25th Amendment language in recent days, amplifying it as a rallying cry. That amplification is politically potent—even when the legal mechanism is unlikely to move—because it puts the vice president and cabinet’s silence under a spotlight.

If Section 4 were invoked, Vice President JD Vance would become acting president immediately. Trump would remain president in title unless Congress ultimately sided with the declaration of inability, or unless other constitutional outcomes took over.

Why invoking Section 4 remains unlikely—even with loud calls for it

The 25th Amendment is not triggered by public outrage. It’s triggered by a specific coalition inside the executive branch.

Three practical barriers dominate:

-

It begins inside the White House.

Section 4 requires the vice president and a majority of cabinet-level officials (or a Congressionally designated body) to sign onto a declaration. Without that internal majority, nothing starts. -

A contested transfer becomes a supermajority test.

If the president challenges the declaration, Congress must settle it. Keeping the president sidelined requires two-thirds votes in both the House and Senate. That’s a higher bar than most major legislative fights and demands a political landscape that is not just divided, but decisively aligned. -

Section 4 has never been used against a president.

Presidents have temporarily handed power to vice presidents under Section 3 for medical procedures. Section 4—removing power without the president’s consent—remains untested in the real-world way people imagine during a crisis.

That’s why the current moment reads more like a pressure campaign than an imminent constitutional transfer: the rhetoric is maximal, the pathway is narrow.

A short timeline of how the 25th Amendment re-entered the news cycle

-

Jan. 18–19, 2026: Trump’s Greenland messaging triggers a new round of alarm over judgment and stability.

-

Jan. 19, 2026: Markey publicly urges invoking the 25th Amendment.

-

Jan. 20–24, 2026: Additional calls and commentary spread, tying the issue to broader concerns about Trump’s conduct and decision-making.

-

Next pivot point: any sign—public or private—of cabinet-level fracture would change the story from symbolic demand to procedural possibility.

For now, the 25th Amendment is doing what it often does in polarized eras: functioning as a constitutional vocabulary word for “this feels dangerous,” more than as a mechanism that’s actually about to fire. But even as rhetoric, it forces a hard question into the open—who, exactly, is willing to say a president can’t do the job, and then prove it under the toughest voting thresholds in American politics?