Ain Country label fuels debate as Russia presses to return to the Winter Olympics

The three-letter tag ain country does not represent a nation, but its meaning has become central as Russia seeks to reassert itself at the Winter Olympics. That debate landed in the spotlight during a program where soft toys rained from the stands and an 18-year-old Russian skater prepared for a second outing.

Ain Country and why the letters matter now

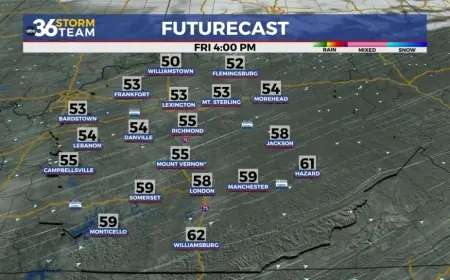

Adeliia Petrosian, 18, drew loud cheers and a deluge of soft toys after the short program, but showed only the faintest of smiles as she finished fifth and prepared to take to the ice again shortly after 9 p. m. Many eyes were on Milano Cortina — and in Moscow — as officials and commentators weighed what a return to full national representation might look like.

Petrosian’s moment: cheers, toys and a tense atmosphere

So far at these Winter Olympics, a Russian is yet to win a medal. Petrosian’s short program left her in fifth place and set up a second skate shortly after 9 p. m. Her performance and the crowd reaction were noted beyond the rink; one broadcaster in Moscow praised her and predicted she would beat everyone, reflecting a broader shift in domestic sentiment.

Two years ago the Kremlin was far less supportive of competitors who did not march under the Russian flag. A small number of Russians competed as “authorised neutral athletes” after vetting to check they did not explicitly support the war in Ukraine, and that stance drew sharp criticism at home. Irina Viner, Russia’s rhythmic gymnastics president, called those who went “traitors” and suggested that only “homeless” athletes competed without their flag and anthem. A rower said the Kremlin had compensated Russian competitors who dropped out.

How Moscow’s tone has shifted and the push for restoration

Moscow’s message has changed. Russia’s press secretary said, “I’ll definitely be watching wherever our guys perform. It’s a must-see. ” A television presenter and Putin loyalist hailed Petrosian as “a great girl, ” saying, “It’s interesting how life changes, ” and noting posters for Olympians in Italy. He used coarse language to describe those who had earlier criticized competing without the flag.

The International Olympic Committee has also moved in recent months. In December it called for Russian youth athletes to be allowed to compete internationally under their own flag, a step that was described as paving the way for participation in the Youth Games. The IOC president said that “every athlete should be allowed to compete freely without being held back by the politics and divisions of their governments. ”

On the Russian side, the sports minister and head of the Russian Olympic Committee predicted an earlier return to competition under the national flag and anthem. He suggested that a restoration could come as soon as April or May and warned that, “If the IOC doesn’t bring our case up for discussion, we will, of course, go to court. ”

The tug of war over representation — whether competitors use a neutral designation or the Russian flag and anthem — has become a live issue at these Games, amplified by visible moments on the ice and vocal commentary at home. There are 13 Russians competing in Milano Cortina, and their results are being watched closely in Moscow.

What happens next is immediate and procedural: Petrosian is scheduled to skate again shortly after 9 p. m., and Russian officials have signaled they will press the IOC on the country’s wider status, with a possible legal challenge if discussions do not proceed. Longer term, officials in Moscow have suggested a return to full national representation could occur in the spring months mentioned above.