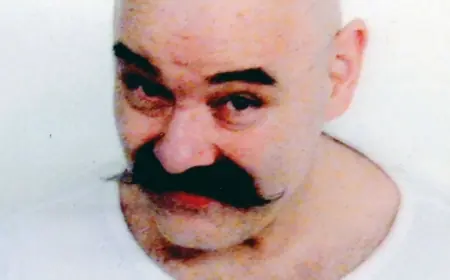

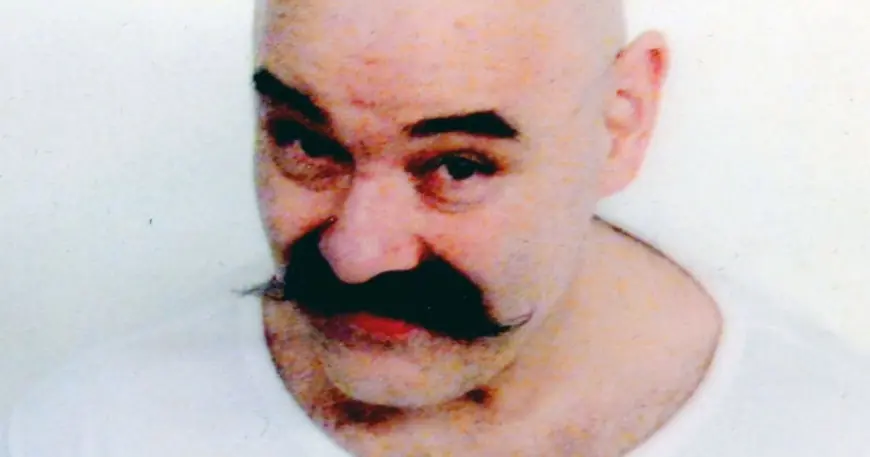

charles bronson trapped in Catch-22 as parole hopes fade after 52 years behind bars

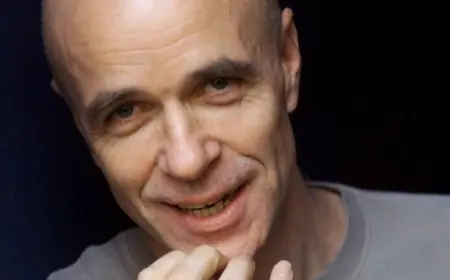

Charles Bronson, one of Britain’s longest-serving and most violent inmates, faces what a former governor calls a Catch-22 as he seeks release. Now 73, Bronson has spent more than five decades in high-security conditions and will make another bid to the Parole Board, but the pathway out of maximum security remains obstructed by his past conduct and limited chances to prove change.

Catch-22: behaviour tested only if moved from high security

Bronson has been held for much of his sentence in Cat A conditions and long periods of solitary confinement after a string of violent incidents spanning decades. Prison officials and psychiatrists who will supply written assessments to the Parole Board will face a central dilemma highlighted by a former governor: unless Bronson is moved into a less restrictive regime his progress cannot be properly tested, but he is kept in maximum security because of his propensity for serious violence.

John Podmore, who once governed at a high-security jail, recalled an attempt three decades ago to place Bronson in a normal cell and work with him to curb outbursts. That experiment ended when Bronson took other inmates hostage, reaffirming the risk assessment that keeps him confined. Podmore described the situation as self-perpetuating — the system will not reduce restrictions without proof of stability, yet the only setting in which stability can be demonstrated is the less restrictive environment the system refuses to grant.

Factors that have changed in recent years — an increase in organised crime, drugs and radicalisation within prisons, and general disorder — make such tests harder to manage and heighten the perceived risk of moving a high-profile prisoner into open conditions. That, his former governor warns, may make the prospects of ever securing release increasingly slim.

Record of violence, refusals and rare glimpses of humanity

Bronson first received a seven-year sentence for armed robbery in 1974 and, with only two brief periods of freedom, has remained in custody due to repeated violent assaults on staff and other inmates. A 1999 incident in which he took a prison art teacher hostage led to a life sentence, and his last conviction for assaulting a governor came in 2014.

Prison life has included spells in secure psychiatric provision as well as time across a number of establishments. Over decades inside, Bronson has written about his experiences and has at times expressed hope of release. He has also changed his name and, in interviews, reflected on formative encounters with notorious inmates from previous eras, describing some prison figures as memorable company during a brutal and isolating life behind bars.

Despite occasional gestures that hinted at remorse or reflection — the former governor noted a condolence card Bronson sent when that governor’s father died — Bronson has also resisted elements of the parole process. Before a recent review he dismissed his legal team and refused to participate after his request for a public oral hearing was declined, later writing that he had sacked his lawyers.

What the Parole Board must weigh

The Parole Board will review written material from prison staff, psychiatrists and probation officers, along with submissions from Bronson’s legal representatives if they are now engaged. The panel may clear him for release, recommend a phased transfer to lower security so his behaviour can be tested, or delay a decision and call an oral hearing to examine matters in more detail.

Any move to open conditions would require confidence that he can be managed safely outside the highest security settings. Given the litany of past violent incidents and the limited opportunities he has had to demonstrate sustained behaviour change outside segregation, that judgement will be difficult. Observers who know the prison system warn that broader systemic pressures within jails add complexity to decisions about high-risk inmates, making the board’s task more fraught than in previous decades.

Bronson’s upcoming appeal is the latest chapter in a long-running saga that raises fundamental questions about how to evaluate change in prisoners who have spent most of their adult lives behind bars and the extent to which prison regimes can or should create the conditions necessary to demonstrate rehabilitation.