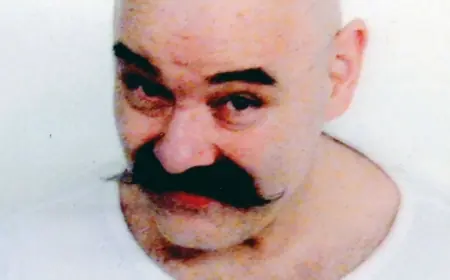

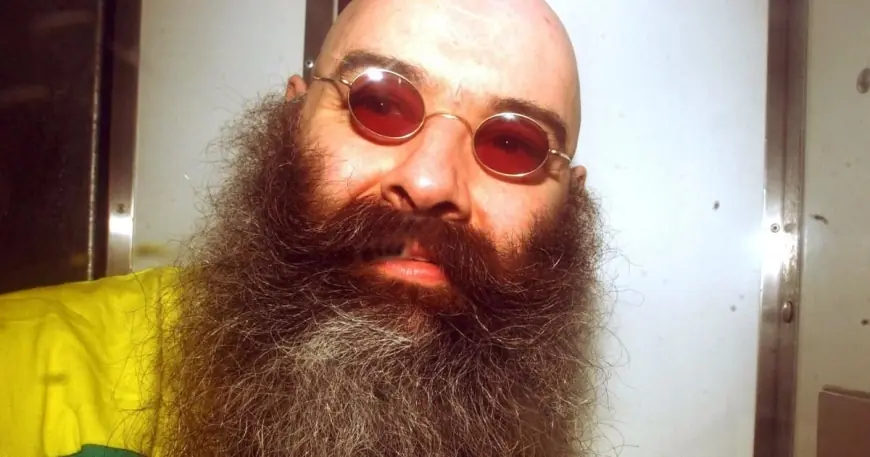

charles bronson reveals his most memorable inmates during 50 years behind bars

Charles Bronson, one of Britain’s longest-serving prisoners, has reflected on a half-century inside custody as he prepares for another parole challenge. The 73-year-old spoke about the inmates who left the biggest impression on him, the advice that stuck, and the thorny parole questions that still shadow his future.

Encounters with icons and gangland figures

Bronson described his time behind bars as at times "horrendous and brutal" but said it also brought him into contact with some of the most notorious figures in the criminal world. He spoke warmly of encounters with the Kray twins, calling them "legends, icons" and praising their loyalty and demeanour. He said their presence stood out above others he met in prisons and secure hospitals across the country.

Over five decades he has been housed in a variety of establishments, including high-security prisons and a psychiatric hospital. He said those years exposed him to "legends" and "great characters" few people ever meet, and that the experience—painful and challenging at times—also brought moments of human connection. "I have lived with them, fought with them, I’ve cried with them, " he said, adding that some relationships were "horrible, sad, and tragic. "

Advice behind bars and how it shaped him

Among the pieces of prison wisdom Bronson highlighted was a blunt line from a fellow inmate known for his toughness: "Don’t think it, do it. " Bronson recalled initially questioning the counsel, then understanding its meaning in the confined, pressure-filled environment of prison life. He said the phrase was meant to prevent obsessive brooding that could drive someone to madness.

He also told of moments that revealed a more complicated side to his character. On one occasion he sent a condolence card to a former governor who had lost a parent—an act the governor said was unique among prisoners. Bronson framed such gestures as evidence that, despite violent incidents in his record, he retains humanity and reflection.

Parole, progress and a persistent Catch-22

Bronson’s prospects remain tightly bound up with parole assessments and his history of violent episodes. He has spent large parts of his sentence in solitary conditions and has repeatedly contested decisions that keep him in the most restrictive regime. Parole panels have previously acknowledged behavioural improvements but have stopped short of recommending moves to less restrictive settings, citing concerns about safety.

Former prison officials have described the dilemma as a Catch-22: he cannot demonstrate sustained, safe behaviour in lower-security settings because he is not being given the opportunity to do so. That dynamic, they argue, makes it ever harder for him to prove he has changed. Bronson recently dismissed legal advisers and expressed anger when requests for a public hearing were denied, underscoring the fraught and personal nature of his ongoing appeals.

Now in his seventh decade, Bronson says he has "no regrets" about his life and that he still holds hope and faith for the future. He remains a polarising figure—hailed by some as a complicated survivor of harsh regimes and condemned by others for a record of violence—but his reflections underline a recurring tension in the criminal justice system: how to balance past behaviour, present rehabilitation, and the practical steps needed to test and verify change.

As he faces another parole review, Bronson’s account of decades behind bars offers an intimate, if controversial, view of life inside high-security institutions: a place where brutal conditions, unlikely friendships, and stark choices coexist, and where the path to release can be blocked by the very restrictions meant to protect the public.