Wuthering Heights movie divides critics over tone, fidelity and its final cut

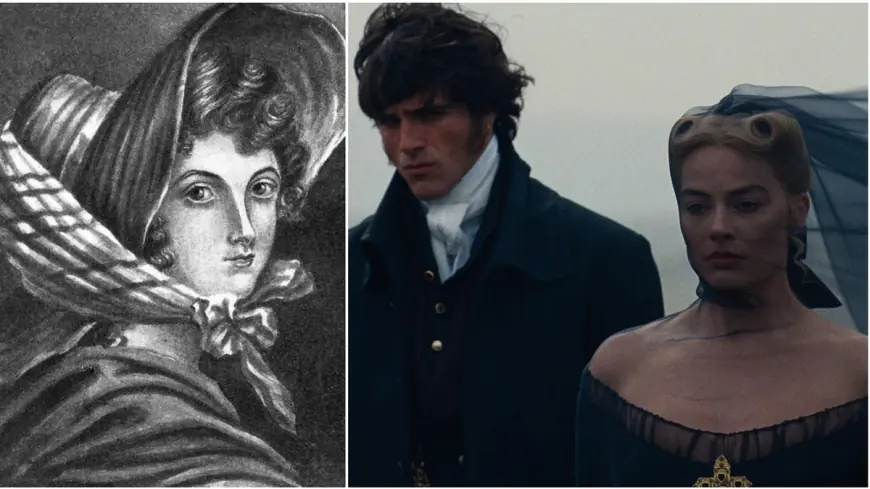

Emerald Fennell’s new Wuthering Heights movie opened this weekend and has quickly become a lightning rod for debate. Reviewers are split between those who applaud a bold, stylized reimagining and those who argue the film sacrifices the source novel’s singular weirdness and generational sweep in favor of camp, sexed-up spectacle and a truncated narrative.

Reworking Brontë: compression, omission and a sharper focus

One of the clearest and most consequential choices in this adaptation is what it leaves out. The film compresses Emily Brontë’s multi-decade, nested narrative into a two-hour arc that stops shortly after the central lovers’ tragedy. The sprawling, second-half storyline about the next generation — the characters who inherit and, in some ways, temper the violence of the first — is almost entirely excised. In the movie, the story culminates with Catherine’s death following sepsis and an apparent miscarriage, closing the door on the novel’s later reconciliation and the possibility of emotional inheritance.

That compression is an editorial move with obvious trade-offs: it intensifies the Cathy–Heathcliff axis, sharpening the film into a single, corrosive romance, but it also removes the longer, restorative arc that many readers regard as essential to the novel’s moral and emotional architecture. The director has framed the film as a one-off, rather than a multi-part epic or miniseries, and the choice leaves the adaptation resolutely focused on immediate passion and ruin rather than on generational fallout.

Style, performance and the charge of losing the novel’s “strangeness”

Critiques cluster around tone and temperament. Detractors find the movie’s approach — high-fashion visuals, explicit sexual depiction and occasional campy flourishes — to be a misfire when applied to Brontë’s strangeness. For some, the novel’s power comes from an oppositional mix of brutality and haunting lyricism: a love that both annihilates and, in time, redeems. The film’s heightened, often playful stylization has been cast as less strange than showy, robbing the story of the ambiguous, unsettling atmosphere that made the book so unlike anything before it.

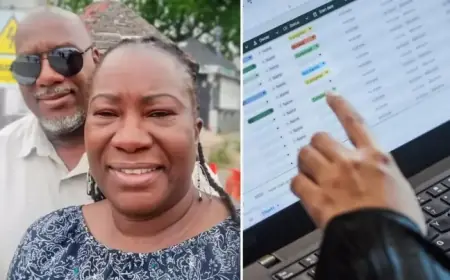

Performances have drawn mixed notices. The leads are polarizing in the way they interpret Cathy and Heathcliff: some critics argue the casting and direction push the characters toward brooding, sexualized archetypes rather than retaining their novelistic complexity. Supporting turns, however, have earned more uniformly positive attention, particularly for actors who lean into idiosyncratic or scene-stealing domesticity and menace. One element singled out for contention is the treatment of Nelly Dean, the novel’s famously unreliable narrator: the film makes her an active, confrontational presence, which changes the dynamics of blame and complicity at the story’s center.

There are also occupational gripes about structural and representational choices. A number of observers noted that certain elements from the book — including aspects tied to class and race as they inform Heathcliff’s outsider status — are de-emphasized or altered, a decision that has prompted debate about fidelity and interpretation.

What the ending change signals for audiences and future adaptations

By ending with Catherine’s death and eliminating the novel’s next-generation reconciliation, the film stakes a claim on what type of story it wants to tell: an intense, self-contained tragedy rather than an epic about legacy and repair. That choice will please viewers who want a focused, visceral romance unencumbered by later plotlines; it will frustrate those who expected the fuller moral and emotional payoff of the original book.

Whether the film’s bold choices will age into appreciation or settle as a contested curiosity remains to be seen. For now, the adaptation has revived familiar conversations about what fidelity to a beloved novel should mean: literal reproduction of plot and structure, or imaginative reimagining that captures something like the original’s spirit. Fennell’s version emphatically chooses the latter, and critics — like audiences — are still deciding whether that spirit survived the translation to screen.