Wuthering Heights movie opens to sharp divide over ending, tone and fidelity

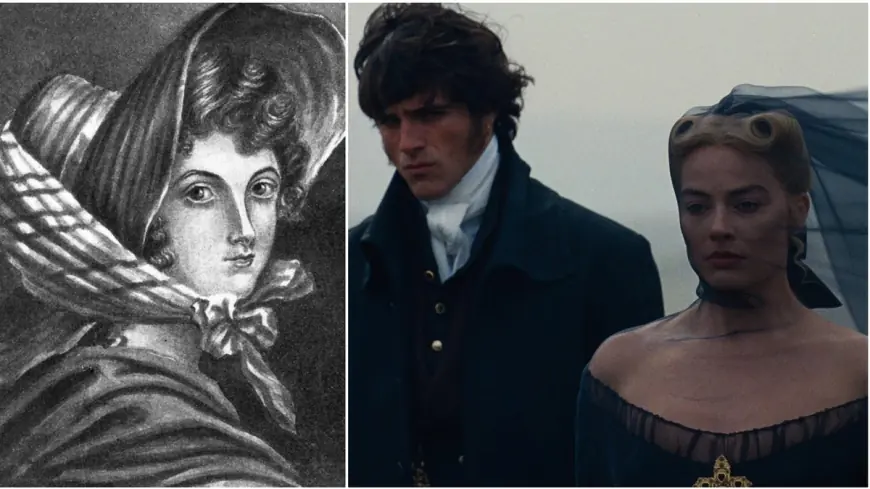

Emerald Fennell’s new Wuthering Heights movie opened this weekend and immediately split critical opinion. The director’s stylized, condensed take on Emily Brontë’s novel — fronted by Margot Robbie as Catherine and Jacob Elordi as Heathcliff — has been praised for its visual bravado and criticized for what some see as a loss of the book’s essential strangeness and generational sweep.

Radical condensation: the missing second half and the film’s ending

Fennell’s adaptation stops roughly midway through the novel and closes on Catherine’s death. In the film Catherine suffers complications that lead to an apparent miscarriage and then dies; the infant who, in the book, grows into the novel’s second-generation reconciliation is never born. That decision removes the later arc in which Cathy’s relationships with Hareton and Linton ultimately temper Heathcliff’s revenge and guide the story toward a troubled kind of redemption.

The director has framed the picture as a standalone work, explaining that Emily Brontë’s dense novel required significant pruning to fit a two-hour cinematic canvas. The choice to end with Catherine’s death makes the movie an intensified portrait of the central pair’s obsession rather than a multi-generational saga. That isolation of the romance is central to the debate: some viewers appreciate the tighter focus on Cathy and Heathcliff, while others see it as an erasure of the novel’s structural ambition and moral complexity.

Tone and style: camp, eroticism and questions of fidelity

Critics are sharply divided on the film’s tone. Many note Fennell’s decision to lean into a heightened, almost fashion-forward aesthetic, with an emphasis on sensuality and theatricality. Scenes that foreground physical desire, bodice-ripping dramatics and a glossy, candy-colored palette have been described as intentionally campy by some reviewers and as emotionally hollow by others.

Performances have drawn mixed responses as well. Margot Robbie’s Catherine is a volatile mix of prim breeding and feral passion; Jacob Elordi’s Heathcliff is presented as a brooding outsider who later returns altered by wealth and purpose. Several reviewers singled out Martin Clunes for scene-stealing turns that shape the film’s tonal center, while Hong Chau’s Nelly Dean was highlighted as a tricky but pivotal reinterpretation of the novel’s chief narrator.

Beyond tone, there is debate over fidelity to Brontë’s text. The film excises or reassigns several characters and plot strands: key elements of Hindley’s downfall are redistributed, some household dynamics are simplified, and the adaptation largely omits the book’s layered narrative structure that relies on nested tellings and an unreliable narrator. Some critics also point to the film’s handling of Heathcliff’s racial ambiguity, arguing the adaptation sidesteps that aspect of the character and the social tensions it implies.

What the split means for audiences and future adaptations

The polarized reception underscores a recurring challenge: translating a famously strange, multi-voiced novel into a single, marketable film. For viewers who approach the movie as a bold reimagining, Fennell’s choices read as a clean re-centering of passion and spectacle. For readers who cherish the novel’s breadth and its uneasy blend of destruction and long-term redemption, the cuts feel like a loss.

By excising the later generations and closing on Catherine’s death, Fennell has largely foreclosed the most obvious route to a direct sequel. Whether the film’s commercial and awards trajectory will encourage more attempts to rework Brontë’s material remains uncertain. What is clear is that Wuthering Heights continues to provoke strong responses — not because it is safely classic, but because every adaptation forces fresh argument about what the story is really asking of its audience.