Why the Lindsey Vonn crash is reigniting debate about racing while injured—risk, reward, and what athletes weigh before “one last run”

Lindsey Vonn’s violent fall in the women’s Olympic downhill on Sunday, February 8, 2026, didn’t just end her run in Cortina d’Ampezzo within seconds. It also reopened one of elite sport’s most uncomfortable questions: when an athlete says “I can go,” who decides whether “can” is the same as “should”?

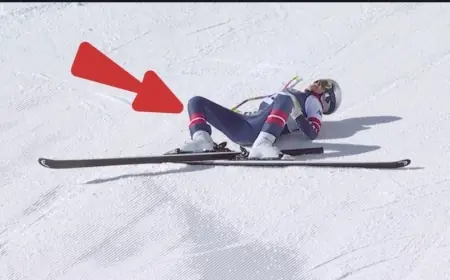

Vonn was airlifted off the mountain for evaluation after crashing early on the course, only days after publicly acknowledging she was racing with a torn ACL in her left knee while using a brace. The optics were stark—an all-time great attempting “one last run” at the sport’s most dangerous discipline, with known instability in the joint most responsible for surviving it.

The crash that changed the conversation

Vonn appeared to lose her line almost immediately, going airborne awkwardly and coming down sideways before tumbling to a stop. Medical teams attended to her on the slope for more than 10 minutes before she was flown away by helicopter.

Even in a sport where falls are expected, this one landed differently. The downhill is already a high-consequence event; pairing it with a fresh major ligament tear makes the margin for safe error feel microscopic. Within minutes, the conversation shifted from medals and legacy to medical risk, duty of care, and whether the sport’s incentives nudge athletes toward choices they might not make in any other workplace.

“Cleared to race” vs. “safe to race”

At the heart of the debate is a gray zone: medical clearance is not a guarantee of safety. It is a threshold decision that often depends on stability tests, swelling, pain tolerance, and whether an athlete can demonstrate functional control under load.

Lindsey Vonn's accident

by u/Ecstatic-Ganache921 in olympics

With an ACL rupture, an athlete can sometimes ski—especially with a brace and strong surrounding musculature—but the knee generally loses a key stabilizer. That can mean subtle compensations that might be manageable in lower-speed settings and much harder to control at 70+ mph on uneven terrain, jumps, and compressions. The risk isn’t only another fall; it’s worsening meniscus damage, cartilage injury, bone bruising, or knock-on injuries caused by altered mechanics.

This is why critics argue the binary framing—either “she’s tough” or “she’s reckless”—misses the real issue. The question is whether elite systems have enough friction built in to slow someone down when adrenaline, identity, and the once-every-four-years clock are pushing the other way.

What athletes actually weigh before “one last run”

No two decisions are identical, but most athletes describe a similar mental spreadsheet—part personal, part medical, part career calculus:

-

Stability and function: Can the joint handle the specific forces of this event, not just daily activity or training?

-

Worst-case downside: What is the realistic risk of long-term damage, not just missing the next race?

-

Competitive upside: Is there a credible path to contending, or is the start mostly symbolic?

-

Support-team alignment: Do doctors, coaches, and federation leaders agree—or is there quiet disagreement?

-

Identity and closure: Is racing a needed final chapter, or is it an obligation to prove something?

Vonn’s situation compressed all of those factors into one tight window: an Olympic start line, a speed event, and a fresh ACL tear.

Incentives that push athletes toward “yes”

Olympics decisions aren’t made in a vacuum. The incentives surrounding a superstar are enormous: sponsors, broadcasters, national pride, teammates who draw momentum from a leader, and the athlete’s own sense of narrative completion. That doesn’t mean anyone is forcing a choice, but it can make “no” feel like letting people down—even when “no” might be the safest answer.

There’s also a competitive reality: downhill skiers spend years building the mental tolerance to attack terrain at full commitment. When injuries happen, the fear isn’t just pain—it’s losing the ability to commit. Some athletes would rather start with imperfect health than step away and wonder forever.

What this could change going forward

Vonn’s crash is likely to intensify calls for clearer guardrails, especially for high-speed events. That could mean more standardized return-to-competition protocols, stronger independent medical authority, or discipline-specific thresholds when ligament instability is involved. It may also lead to more open conversation about mental readiness—because fear, confidence, and risk tolerance can change as much as ligaments do.

For now, the sport is left with an uneasy truth: the same mindset that makes champions—relentless belief, pain tolerance, refusal to quit—can also pull them toward the edge. When the goal is “one last run,” the hardest part is knowing when the run itself becomes the risk.

Sources consulted: Reuters, Associated Press, Scientific American, CBS News