What time is the annular solar eclipse on Feb. 17? solar eclipses in Antarctica explained

On Feb. 17 (ET), the moon slid between Earth and the sun and produced an annular solar eclipse — the dramatic "ring of fire" effect that occurs when the lunar disk is too small to completely cover the sun. The spectacle lasted only a few minutes at most along a narrow Antarctic corridor and was visible as a partial eclipse across wider southern latitudes.

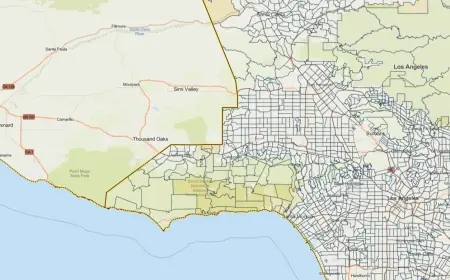

Where the annular eclipse was visible

Only a sliver of Antarctica fell inside the path of annularity — a corridor roughly 2, 661 miles long and 383 miles wide (4, 282 by 616 kilometers). Within that swath, observers saw the moon obscure about 96% of the sun, leaving a bright outer ring at maximum eclipse for up to about 2 minutes and 20 seconds at the greatest eclipse.

Outside the narrow path, much of Antarctica and portions of southern Africa and the southernmost tip of South America witnessed a partial solar eclipse. For most skywatchers beyond the annular track, the sun appeared as a crescent for a portion of the event rather than forming a complete ring.

Satellites captured striking views of the moon's shadow sweeping across the frozen continent, offering dramatic confirmation of the eclipse for anyone who could not observe it from the ground.

When and what to expect

The annular phase was brief — measured in minutes — but the full eclipse sequence, from the initial partial phases through the end of the partial phases, stretched longer as the moon's silhouette moved across the sun. At greatest eclipse the bright ring, or annulus, stood out sharply against the solar disk, creating one of the most photogenic solar phenomena skywatchers can hope to see.

For observers in the corridor of annularity the central effect was unmistakable: the moon’s apparent diameter was just small enough that a luminous rim of sunlight encircled the dark lunar disk. Elsewhere in the partial zone the sun took on a pronounced bite out of its face, with the amount of obscuration increasing with proximity to the annular path.

This event rounds out a series of notable eclipses on the astronomical calendar. The next solar eclipse of major interest will be a total solar eclipse on Aug. 12, 2026 (ET), crossing parts of Greenland, Iceland and northern Spain, with a broader partial view across Europe and Africa. A total lunar eclipse on March 3, 2026 (ET) will also turn the moon a deep red for observers across North America, Australia, New Zealand, East Asia and the Pacific.

How to view solar eclipses safely

Never look directly at the sun without certified solar filters. Whether an eclipse is annular or partial, the risks to eyes are the same: permanent damage can occur if appropriate protection is not used. Observers must use solar eclipse glasses that meet international safety standards, and cameras, telescopes or binoculars require proper solar filters fitted in front of the optics at all times.

Do not rely on improvised darkening materials or ordinary sunglasses. Pinhole projectors and other simple projection methods offer a safe, indirect way to experience an eclipse’s progress without exposing eyes to direct sunlight. If using photographic or telescopic equipment, double-check that filters are secure and intact before any part of the sun is visible through the instrument.

For those who could not travel to the Antarctic annular track, satellite imagery and post-event photos and videos provide the clearest record of the eclipse’s passage. Photographs captured from space showed the deepening shadow on the ice and the moon’s disk silhouetted against the sun — potent reminders of the orbital mechanics that produce solar eclipses and of the care required to view them safely.

As always with rare sky events, planning matters: know your local viewing conditions, confirm proper protective gear, and mark future eclipse dates if you hope to chase the next ring of fire or totality.