Emerald Fennell’s Wuthering Heights Sparks Fresh Debate Over Ending and Tone

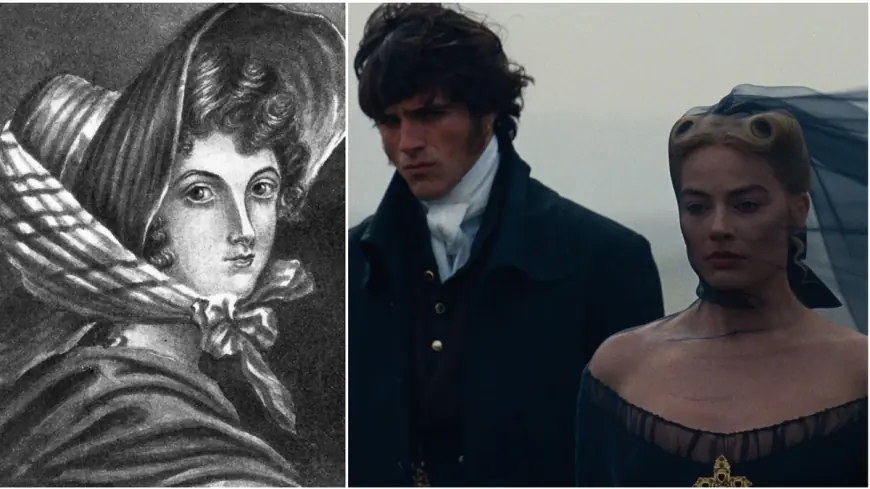

Emerald Fennell’s new adaptation of Wuthering Heights opened this weekend and has already provoked strong reactions. The film compresses Emily Brontë’s decades-spanning novel to focus tightly on Catherine and Heathcliff’s volatile relationship, a choice that preserves intensity for some viewers and feels like an erasure of the book’s larger architecture to others.

What was cut — and why it matters

The most consequential change in the film is structural: Fennell stops the story roughly where the novel’s first great arc concludes. Catherine’s death in the movie follows an apparent miscarriage and sepsis, and the infant who figures in the book’s second-generation drama never appears. That omission removes the novel’s lengthy exploration of legacy, revenge, and eventual partial healing through the younger characters.

Fennell has framed the choice in pragmatic and artistic terms. She has described the novel as “dense” and said that adapting the whole work for a single two-hour film required sacrificial cuts — “I had to kill a lot of my own darlings, ” she explained. For the director, the heart of the story is the destructive, all-consuming bond between Catherine and Heathcliff, and trimming the later material was a way to preserve the film’s central emotional engine.

The consequence is a film that closes on a moment of private catastrophe rather than on the novel’s longer reckoning with inheritance and small acts of redemption. That decision also forecloses the obvious path to a sequel: without the younger generation present, the plot threads that drive the book’s second half do not exist in this telling.

Debate over fidelity, tone and the novel’s ‘strangeness’

Reaction has divided along predictable lines. Some viewers welcome a concentrated, modernized rendering of the central romance, praising the film’s visuals, its contemporary impulses and its refusal to dilute the main couple’s chemistry. Others argue the adaptation misfires as an interpretation of the novel’s essence: they contend that the book’s defining quality is not merely its plot but its sustained weirdness — an unsettling blend of lyricism, cruelty, and the uncanny — and that the movie flattens that singularity into something more conventional.

One high-profile critical appraisal described the film as a disappointment specifically as a love story, arguing that by stripping away the novel’s generational scope and some of its gothic oddities, the movie loses the mixed, contradictory sense of love that made the original so disorienting and memorable. That line of critique frames fidelity not as slavish recreation of events but as preservation of tone, architecture and moral ambiguity.

Defenders of Fennell’s choices counter that cinematic form imposes limits and that adaptation requires reimagining. The director has acknowledged that the story could be told in other formats — there is “a world where this is a miniseries, ” she observed — but has also said she intended this project as a one-off, focused statement about the pair at the center of Brontë’s novel.

Whatever side viewers take, the film has reopened a familiar question about classic adaptations: must a screen version replicate every plot beat to be faithful, or can it be true to a book’s spirit by pruning and intensifying? Fennell’s Wuthering Heights embraces the latter route, and that choice is shaping conversation as the movie finds its audience this opening weekend.

Whether the film will prompt further adaptations that attempt the whole novel or inspire debate about longer-form versions remains to be seen. For now, it has returned Brontë’s strange, stubborn work to the cultural conversation — and reignited an argument about what it means to make a faithful adaptation in the 21st century.