Emerald Fennell’s Wuthering Heights Split Critics by Cutting the Saga Short

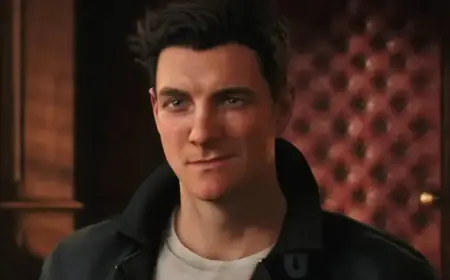

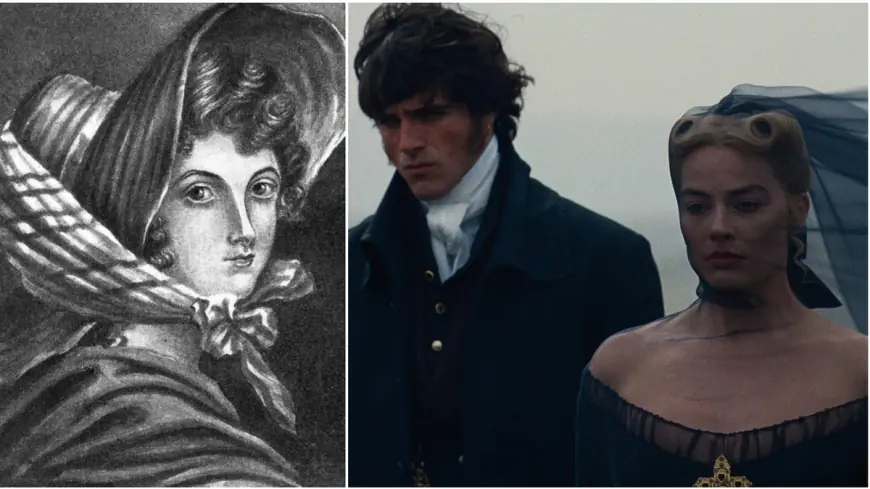

Emerald Fennell’s hotly anticipated adaptation of Wuthering Heights opened this weekend (Eastern Time), and reaction has been sharply divided. The film reimagines Emily Brontë’s storm-tossed novel with a vivid, candy-colored palette and a tightened focus on Catherine and Heathcliff. But the director’s choice to end the movie midway through the book — and to excise the next-generation storyline entirely — has prompted fresh debate about what counts as fidelity, romance and cruelty in cinematic versions of classic literature.

A fierce, compressed central romance — and a different ending

Fennell’s film narrows the sprawling 19th-century epic to the volatile relationship between Catherine and Heathcliff. Where the novel continues into the lives of their children and the slow unspooling of generational consequences, the movie stops near the emotional apex: Catherine’s decline and death. The adaptation replaces the novel’s childbirth and the subsequent arc of Cathy, Hareton and Linton with a fatal miscarriage and a montage that collapses years of passion and vendetta into a single, elegiac sequence.

That choice is both pragmatic and aesthetic. With roughly two hours of screen time, Fennell trims subplots that would require a miniseries to fully realize. The director has framed the film as a one-off, prioritizing the erotic and violent chemistry between the leads over the later reckonings that make the novel multigenerational. Viewers expecting a faithful chronicle that culminates in a generational reconciliation will be surprised; those seeking a distilled, modern take on the core relationship will find deliberate, sometimes provocative stylistic choices.

Critics clash over strangeness, romance and fidelity

Critical voices have clustered around two main objections. One set argues that the adaptation’s visual bravado — bright, almost licorice-hued production design and heightened eroticism — feels at odds with the novel’s bleak, uncanny strangeness. For these critics, much of Brontë’s power derives from a tone that is simultaneously brutal and ghostly; stripping out the second half and bathing the first in saturated aesthetics saps the book’s singular weirdness.

Others defend the adaptation as a creative condensation that captures the emotional core of the story. They point out that filmmakers have long faced the impossibility of shoehorning a dense, nested narrative into a standard feature length. From early silent attempts to later television and film versions, storytellers have repeatedly chosen to emphasize either the doomed lovers or the aftermath. Fennell’s film lands squarely in the former camp: a focused, sensual tragedy that closes with Catherine’s death and refuses to dirty itself with the slow-building familial retribution that fills the novel’s second half.

The debate also raises larger questions about adaptation as interpretation. Is a movie judged by how closely it matches plot beats, or by whether it evokes the spirit of the source? Fennell’s answer appears to be: pick a spine, and feel it fully. For some viewers, that produces a concentrated experience; for others, it feels like an unfinished novel given glossy treatment.

Where this film sits in the Wuthering canon

Wuthering Heights has always been a tempting, slippery property for filmmakers. Its themes of obsession, revenge and landscape-as-character invite stylization and bold choices. The new film contains echoes of earlier takes that favored condensation or emphasized the sexual ferocity of the central pair, but it stands out for how explicitly it severs the story’s line into the next generation.

For audiences, that severing has consequences. Without the later reconciliation and the eventual softening that rounds the novel’s arc, this adaptation presents love almost exclusively as a destructive force — intense, unforgettable and ultimately terminal. Whether that framing constitutes a deficiency or a deliberate reimagining depends on what viewers bring to the screen: a longing for mythic strangeness, or a desire for tidy narrative closure.

As conversations continue through the weekend and beyond, one thing is clear: Fennell’s Wuthering Heights has reignited interest in how modern filmmakers handle 19th-century classics. For some, the film is a bold, concentrated artwork; for others, it is a stylish but incomplete translation of a singularly strange novel.