Jmail and the Jeffrey Epstein files PDF: A Gmail-style viewer reshapes access and debate

A surge of searches for “jmail” and “jeffrey epstein files pdf” is being driven by a simple reality: the newest federal document dump tied to Jeffrey Epstein is so large that many people can’t easily navigate it in its original format. A third-party tool known as Jmail has stepped into that gap with a familiar, webmail-style interface that makes selected records feel searchable and “inbox-like,” even though the underlying material comes from public releases.

The shift is changing how the public consumes the documents—faster scanning, more screenshots, and more viral claims—while raising fresh questions about context, completeness, and the risks of misinformation.

What Jmail is, and why it’s spreading

Jmail is a browser-based archive that presents portions of Epstein-related releases in a layout styled like an email inbox. Instead of downloading huge PDFs and hunting manually, users can browse, filter, and search through indexed text that has been extracted from the public documents.

That usability is the appeal. For many people, an inbox interface is instantly intuitive, while an official library of massive PDFs is not. The result is a dramatic reduction in friction: it’s easier to jump from name to name, skim threads, and share a single highlighted page—exactly the kind of behavior that drives social media amplification.

The scale problem: why “the PDF” isn’t one file

A core misunderstanding behind many viral posts is the idea that there is a single, definitive “Epstein files PDF.” In practice, the release is an evolving collection of many files, often organized in batches or “volumes,” and drawn from different investigative and prosecutorial sources.

On Jan. 30, 2026, the U.S. Department of Justice announced it had published 3.5 million additional pages in response to the Epstein Files Transparency Act. That kind of scale creates real barriers for everyday readers: large downloads, inconsistent scanning quality, redactions, and repeated or near-duplicate pages that can confuse even careful viewers.

What the newest documents are (and aren’t) showing

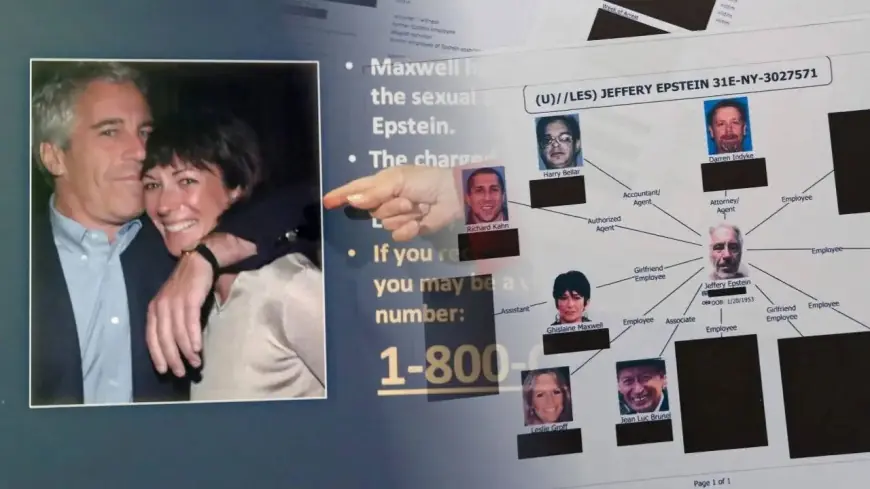

The latest wave of attention is also tied to what people hope to find: a definitive roster of powerful clients or a single “smoking gun” document. But recent document-based analysis in mainstream coverage has emphasized something more mundane and, for some, unsatisfying: investigators documented extensive abuse by Epstein, yet the evidence did not support some of the broadest public rumors in the way many online posts imply.

In particular, recent analysis has stressed that a widely circulated notion of a formal “client list” does not match what investigators said they found in the records. At the same time, the documents include a wide range of material—memos, administrative records, correspondence, exhibits, and images—that can contain prominent names without establishing criminal conduct. Presence in a file can reflect contact, investigation, rumor, or routine administrative context.

Why details can look inconsistent across PDFs and “inbox” views

Even when the source documents are authentic, formatting and processing can distort what readers think they’re seeing:

-

Scanning and text extraction artifacts: Automated text capture can misread names, dates, and punctuation—especially from low-quality scans—making a line look more definitive than it is.

-

Multiple versions of the same record: Different redaction passes and duplicates can make it appear as though a document “changed,” when it’s actually a second copy processed differently.

-

Thread context missing: Email-like presentation can encourage readers to treat a single message as a complete story, even when the full chain or attachment context is elsewhere in the release.

This is where Jmail’s convenience cuts both ways: it makes discovery easier, but it can also accelerate decontextualized sharing.

What to watch for: scams and “unredacted PDF” bait

High-interest public records are a magnet for scams, and the Epstein release is no exception. The most common traps are sites promising “full unredacted PDFs,” “hidden videos,” or “exclusive leaks” that require downloads, browser extensions, or personal information.

Key takeaways for safer reading

-

Treat “unredacted” claims skeptically unless they clearly match official publication channels.

-

Avoid prompts that ask you to install software or enter payment details to “unlock” files.

-

If a claim relies on a single screenshot, assume missing context until you can verify surrounding pages in the underlying release.

Why the conversation is intensifying now

Two forces are colliding in early February 2026: the sheer size of the Justice Department release and the public’s demand for quick answers. Tools like Jmail are filling a usability gap, while lawmakers are also pressing for access to more complete or less-redacted materials under controlled conditions.

The near-term trajectory is likely to be more of the same: more indexing, more reposting, and more disputes over interpretation. The most meaningful developments will be the ones tied to verifiable, date-stamped actions—formal filings, official statements, and clearly attributable records—rather than viral fragments circulating without context.

Sources consulted: U.S. Department of Justice, Associated Press, WIRED, Congress.gov