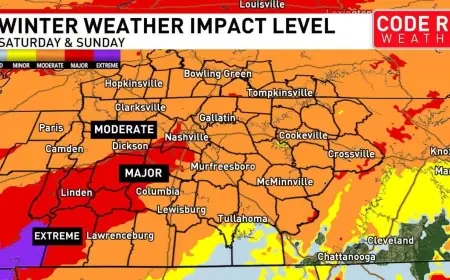

National Weather Service warnings turn urgent as a massive winter storm tests how fast people can act

A sprawling winter storm is pushing the National Weather Service (NWS) into its most consequential role: not just predicting weather, but compressing decision-making for tens of millions of people into a few hours. With heavy snow, damaging ice, and dangerous cold spreading across a wide swath of the U.S., the practical question isn’t whether the forecast is dramatic—it’s whether households, utilities, road crews, airlines, and local officials can move quickly enough to reduce injuries, outages, and travel chaos.

When the forecast becomes a logistics problem

This storm’s footprint is so large that “local impacts” now mean regional chains: a highway closure in one state can ripple into supply delays, stranded travelers, and slower emergency response hundreds of miles away. The NWS has been issuing a layered stack of alerts—winter storm warnings, ice storm warnings, extreme cold warnings—because the hazards are different depending on where you are and when the worst conditions arrive.

Here’s the part that matters: ice is the force multiplier. A few millimeters of glaze can turn roads into skating rinks and bring down tree limbs and power lines, while cold snaps make outages riskier and pipe damage more likely. In areas under extreme cold warnings, the danger isn’t just discomfort—wind chills can create frostbite risk in a short time, especially if someone gets stranded or loses heat.

What’s easy to miss is how much of public safety depends on message delivery, not meteorology. The most accurate warning still fails if people can’t access radar, don’t receive weather radio alerts, or assume conditions will match the last storm they remember.

The storm picture: ice, snow, and cold across a long corridor

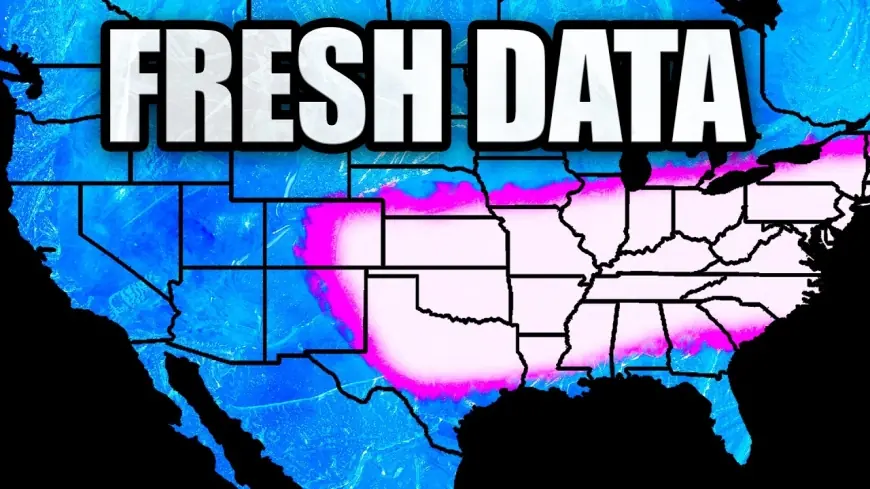

Emergency declarations have spread across a growing list of states as the storm’s impacts broaden. Forecasts show a long, continuous corridor of winter hazards stretching roughly 2,000 miles, with ice and mixed precipitation in some southern zones, heavy snow in parts of the Plains and Midwest, and plowable snow plus bitter cold spreading into northern and northeastern areas.

In parts of Texas and nearby states, NWS offices have highlighted the highest-risk combination: freezing rain on top of already-cold ground, followed by prolonged subfreezing temperatures. That sequence can lock in dangerous road conditions for longer than people expect and complicate restoration work if power lines and trees come down.

Farther north and east, the storm threat shifts toward heavy snow and drifting, with cold pushing behind it. In several regions, the cold is not just “below normal” but potentially hazardous for anyone outdoors for long—especially children, older adults, and people without reliable heating.

Airlines have already moved into disruption mode, urging travelers to rebook and preparing for cascading cancellations around major hubs. If you’re traveling, the limiting factor often becomes ground operations—icing, runway treatment, crew repositioning—not just what’s happening in the sky.

Mini timeline of the storm’s operational pressure points:

-

Late week into the weekend: expanding ice and winter storm warnings in southern and central zones, with rapid deterioration of roads.

-

Weekend into early week: heavier snow and stronger cold signal expanding east and north, increasing the chance of multi-day disruptions.

-

After the main band passes: residual hazards—refreeze, wind-driven drifting, and restoration delays—can linger even when skies clear.

The real test will be whether communities can keep pace with a storm that changes character as it travels.

A quieter vulnerability: radar and alert delivery during peak demand

While the storm itself is the headline, the NWS ecosystem has been dealing with the less visible realities of keeping nationwide tools running during high-traffic moments. The NWS radar website has faced outage messaging in recent days, a reminder that the public-facing side of weather intelligence can become strained precisely when demand spikes.

Separately, individual radar sites do go offline from time to time due to maintenance or hardware issues. When that happens, forecasters typically rely on overlapping coverage from nearby radars, satellite data, surface observations, and other sensor networks to maintain warning operations. But the loss of a nearby radar can still reduce local detail—particularly for fast-evolving hazards like ice bands, narrow snow corridors, or rapidly changing precipitation type near the freezing line.

NOAA Weather Radio—often the backbone for alerts during power and internet disruptions—also experiences localized outages and scheduled downtime. Even a planned service interruption can matter during a major storm window, which is why redundancy is essential: phone alerts, local emergency notifications, and multiple forecast access points.

Key takeaways for the public during this storm:

-

Treat ice forecasts with extra seriousness; small accumulation ranges can lead to outsized impacts.

-

Plan for multi-day disruptions even if the main snowfall window looks short.

-

If you rely on radar or weather radio, have a backup method ready before conditions deteriorate.

-

Assume refreezing after precipitation ends can be as hazardous as the initial storm.

The National Weather Service can’t shovel roads or repair power lines—but its warnings shape whether those crews are staged early, whether travelers delay a trip, and whether families prepare before the first glaze of ice hits the driveway. In a storm this big, that timing is the difference between inconvenience and emergency.