Sydney shark attacks: uncertainty rises after Nico Antic’s death and a rapid cluster of bites across beaches and harbour

Sydney’s summer shoreline has shifted from routine risk to public unease after a fast-moving run of shark incidents culminated in the death of 12-year-old Nico Antic, attacked in the harbour near Shark Beach at Nielsen Park, Vaucluse. The immediate impact is being felt far beyond a single cove: beaches have cycled through closures and reopenings, families are rethinking “safe” swim spots inside the harbour, and surf communities are confronting how quickly a normal session can become a mass first-aid response.

A weekend of grief, and a coastline trying to recalibrate

Nico Antic died in hospital after being bitten on January 18, 2026, while in the water near Shark Beach in Sydney’s east. The attack occurred outside the netted swimming enclosure and is believed to have involved a bull shark. Friends helped pull him from the water and first aid was provided before he was taken to hospital, but he did not survive.

The tragedy has landed in a broader context: four shark-related incidents along the New South Wales coast within roughly 48 hours have rattled public confidence and triggered heightened surveillance and public warnings. Even when beaches reopen, the emotional bar for returning is higher—especially for parents, and especially in areas where swimmers assume the harbour is safer than open surf.

Community support for the Antic family has also surged, with a fundraising campaign drawing hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations and messages of support in recent days.

The pattern behind the “fourth shark attack” headlines

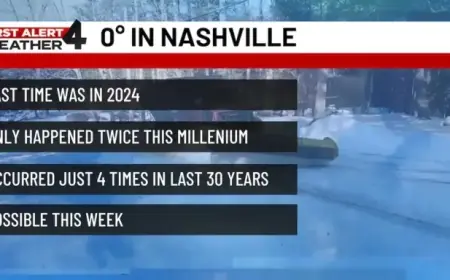

The cluster that has dominated Sydney news this week spans different settings—harbour swim spots, open beaches, and the Mid North Coast—yet the common thread is a run of conditions that can increase encounters.

Recent heavy rainfall has churned up and darkened nearshore waters, flushing debris and nutrients into the ocean. Murkier “dirty water” can reduce visibility and draw baitfish closer to shore, creating a setting where bull sharks—a species known to move through rivers, estuaries, and harbours as well as surf zones—are more likely to be near people.

Across Sydney and the Mid North Coast, the incident list includes:

-

Vaucluse (Sydney Harbour): Nico Antic, 12, fatally injured near Shark Beach at Nielsen Park on Jan. 18.

-

Dee Why (Northern Beaches): An 11-year-old was not injured after a shark bit chunks from his surfboard on Jan. 19, prompting an immediate alarm and response.

-

Manly (Northern Beaches): Andre de Ruyter, 27, was bitten while surfing on Jan. 19 and remains in intensive care; the injury required major medical intervention.

-

Point Plomer (Mid North Coast, near Crescent Head / Port Macquarie region): A 39-year-old surfer was bitten on Jan. 20 and treated for cuts and grazes.

By Jan. 24, fresh shark sightings again prompted temporary closures at Manly and Garie Beach before reopenings, reinforcing how quickly conditions can change from “all clear” to “out of the water.”

Mini timeline

-

Jan. 18: Nico Antic is attacked in Sydney Harbour near Shark Beach, Vaucluse.

-

Jan. 19: Dee Why board bite incident; later the same day, Andre de Ruyter is attacked at Manly.

-

Jan. 20: Point Plomer surfer bitten on the Mid North Coast.

-

Jan. 24: Manly and Garie Beach briefly close again after sightings, then reopen with stepped-up patrols.

-

Next signal: A sustained drop in sightings after water clarity improves would be the clearest sign that the heightened risk period is easing.

What changes right now for swimmers and beach operations

The practical response has been a visible ramp-up in detection and deterrence: more aerial patrols, expanded monitoring during peak holiday crowds, and a tighter posture on closures when sharks are sighted close to shore. The aim is not to promise zero risk—no ocean program can—but to shorten the time between a shark’s appearance and a clear instruction for people to exit the water.

For the public, the hardest adjustment is psychological. A single incident is often processed as rare misfortune; a cluster compresses fear into routine decision-making. In Sydney’s case, the presence of a fatal harbour attack has also challenged assumptions about sheltered swim areas, even those near nets and designated swimming zones.

While summer crowds will keep returning—especially over long-weekend weather—this week’s events have created a new, uneasy baseline: swim plans are now being made around alerts, visibility, and patrol presence, not just tide and temperature.