Annular Solar Eclipse Paints a Fiery Ring Over Remote Antarctic Corridor

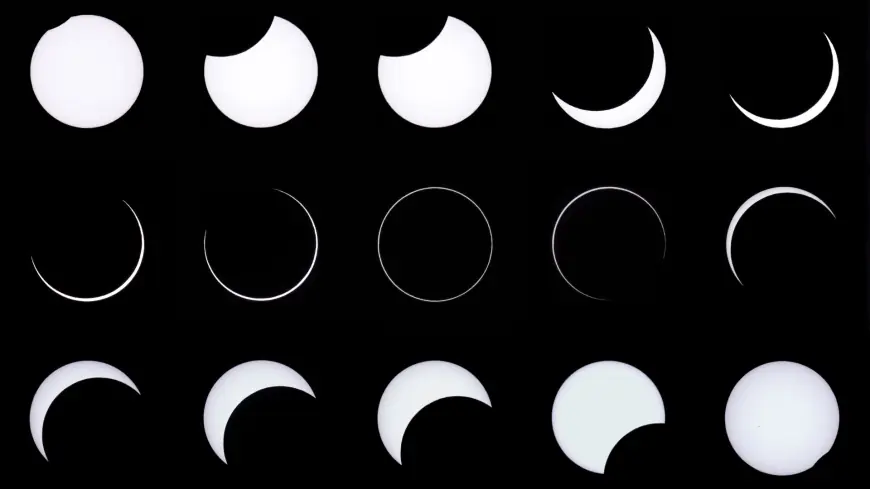

On Feb. 17 an annular solar eclipse swept across a remote swath of Antarctica, briefly turning the sun into a glowing ring for observers in the narrow path of annularity. The event highlighted the precise celestial choreography of the sun, moon and Earth and offered a stark reminder of both the spectacle and the viewing risks of solar eclipses.

What unfolded over Antarctica

The eclipse began when the moon moved between the sun and Earth during its new moon phase. The alignment took place while the moon was near the far point of its elliptical orbit, making its disk appear slightly smaller from Earth and preventing it from fully covering the solar surface. The partial obscuration progressed until annularity — the moment the sun appears as a bright ring encircling the lunar silhouette — was reached.

The event got underway at 4: 56 a. m. ET, with the moon eating a growing bite from the solar disk and reshaping the sun into a crescent before annularity formed. That ring phase lasted a little over two minutes and traced a narrow corridor roughly 383 miles (616 kilometers) wide across the Antarctic continent. The path passed near isolated research outposts, including one that typically hosts fewer than one hundred scientists and visitors at a time, offering an extraordinarily rare front-row view for a very small community.

After annularity ended, the moon continued along its track and the sun returned to its usual appearance as the eclipse concluded at 9: 27 a. m. ET when the lunar silhouette finally cleared the solar disk.

Who saw the eclipse and why it looked the way it did

While only a tiny fraction of people were directly under the annular corridor, a broad swath of the Southern Hemisphere experienced a partial eclipse. An estimated 176 million people — roughly 2 percent of the global population — were within regions that witnessed at least a partial obscuration of the sun, including parts of the southern tip of South America and nations in southern Africa and surrounding islands.

The distinctive "ring of fire" appearance stems from geometry. The moon’s orbit is elliptical, so its apparent size in Earth’s sky varies. When a new moon aligns with the sun while near apogee, its apparent diameter is slightly smaller than the sun’s. That size difference allows the sun’s bright outer edge to form a ring around the moon at maximum alignment, producing the annular effect rather than totality.

Observers within the narrow band experienced the peak annularity for only minutes, while those farther afield saw the sun dimmed into a crescent for longer periods as the moon’s shadow swept across the region.

Viewing safety and what’s next

Solar eclipses demand careful eye safety. Direct viewing of the sun without certified eclipse glasses or solar filters can cause serious and permanent eye damage. Only during the very brief moments of totality in a total solar eclipse — not during annularity — is it safe to look at the sun without protection, and only while the sun is completely obscured. For all other phases of a solar eclipse, proper solar viewers, filters for cameras and telescopes, or indirect viewing methods should be used.

Skywatchers have more celestial events to look forward to: a total lunar eclipse, often called a "blood moon, " will occur early on March 3 and will be visible to large portions of the globe without eye protection; later in the year, a total solar eclipse on Aug. 12 will cross other regions and will again require eye-safe viewing practices for those hoping to witness totality.

The Feb. 17 annular eclipse served as a compact demonstration of orbital mechanics and a reminder that, while many celestial events are visible only to a few, their reach and resonance are felt by skywatchers everywhere.