Mars Organic Molecules Discovery: Non‑biologic Sources Fall Short, Study Finds

Researchers say the amounts of decane, undecane and dodecane detected in a mudstone sample from Gale Crater are larger than expected from known abiotic delivery and production mechanisms, prompting renewed interest — and caution — about whether life could have produced them. The analysis, published Feb. 4, 2026 ET, combines rover data, laboratory radiation experiments and mathematical modeling to estimate how much organic material the rock originally contained.

What was found and why it matters

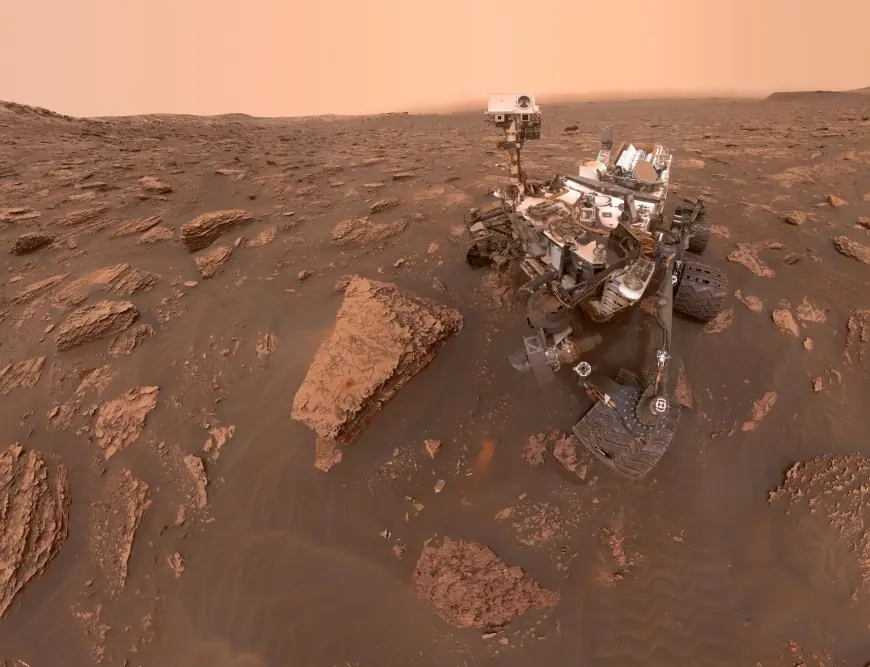

In March 2025, the chemistry laboratory aboard a surface rover analyzing a drilled rock in Gale Crater detected the largest organic molecules yet identified on Mars: three long‑chain hydrocarbons — decane, undecane and dodecane. On Earth, these compounds can be fragments of fatty acids, which are commonly produced by life but can also form through geologic and photochemical pathways.

Because the rover's suite could not conclusively determine a biological origin from the sample alone, the research team set out to test whether all plausible non‑biological sources could account for the measured abundances. The outcome of that exercise has direct implications for how scientists interpret the chemical signatures preserved in ancient Martian rocks and for priorities in future life‑detection efforts.

Rewinding Mars: experiments and models

To estimate the rock's original organic inventory, researchers simulated 80 million years of surface exposure — the time the sampled mudstone likely spent at or near the surface where cosmic radiation and solar particles gradually break down organics. The team combined controlled laboratory radiation experiments, which measure degradation rates under Mars‑like conditions, with mathematical models that extrapolate how much material would be destroyed over geologic time.

They then compared that reconstructed starting abundance with the amount that could reasonably be delivered or produced by known abiotic routes: interplanetary dust and meteorite deposition, atmospheric haze fallout, hydrothermal and serpentinization reactions, and other geochemical processes. Even when summed, these mechanisms could not approach the inferred original quantity of long‑chain organics.

Carbonaceous meteorites — a major carrier of complex organics to planetary surfaces — were evaluated as a likely delivery vehicle. The team found such impacts could contribute material, but not in the volumes required by the back‑calculation from the surviving organics in the sample.

Implications and next steps

The shortfall in plausible non‑biological inputs leaves open the reasonable hypothesis that biological processes could have formed at least some of the molecules now observed in the mudstone. The researchers stress that this is not a claim of detected life, but rather that the observed abundances are difficult to reconcile with currently understood abiotic pathways.

Key uncertainties remain. Laboratory simulations of radiation‑driven degradation are imperfect proxies for complex in‑situ conditions, and rates of breakdown for specific molecules in Mars‑analog rock matrices need tighter constraints. The team highlights the need for more experiments that mimic Martian mineralogy, burial histories and variable radiation environments to reduce those uncertainties.

These findings also underscore the value of returning pristine samples to laboratories on Earth, where more sensitive and varied techniques could probe molecular structures, isotopic signatures and contextual mineralogy that are beyond the capabilities of current rover instruments. Until such data are available, the origin of these long‑chain organics remains an open and provocative question.

For now, the study tightens the net around what can be explained by non‑biologic chemistry and renews scientific attention on Mars as a planet that once hosted complex organic chemistry — and, possibly, the conditions for life.