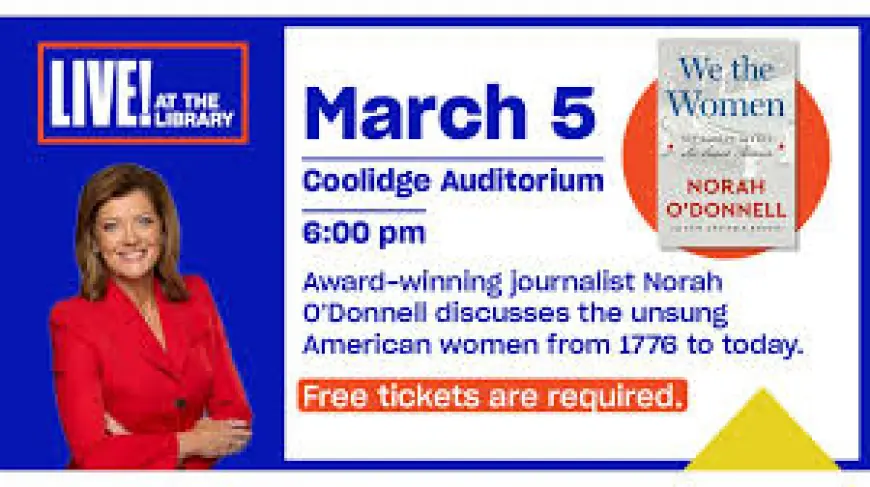

Norah O'donnell Recasts American Memory: How a New Book Forces a Rethink of Women’s Hidden Roles

Norah O'Donnell is asking readers to revisit familiar milestones with unfamiliar eyes, and that matters now because her book arrives as libraries spotlight Women's History Month. In We the Women, O'Donnell frames overlooked lives—from a printer who put a woman's name on a Declaration broadside to midcentury breakthroughs—in a way designed to change what people assume about who shaped the nation's story.

Why Norah O'Donnell frames the past differently

This is a contextual rewind: the book is driven by O'Donnell's surprise at gaps in her own education, which she highlights to explain why conventional history often misses women's contributions. What’s easy to miss is how small, explicit acts—printing a document, insisting on a speaking slot, drafting rights-focused legislation—become doorways to larger institutional change when they are placed back into the narrative.

Book highlights and embedded event context

The book collects profiles of women who appear in official records but rarely in standard classroom timelines. Examples include a Civil War surgeon who earned the nation's highest military honor, the legislator responsible for landmark gender-equality school law, and early female pioneers in sports and government service. A striking episode revisits the first official printing of the Declaration of Independence that bears the name of a woman printer, demonstrating that a female-run business participated in revolutionary publishing.

O'Donnell also foregrounds a dramatic 1876 moment at Independence Hall, when suffragists—denied roles in centennial programming—staged their own reading of a "Declaration of the Rights of Women. " The book traces the arc from that protest to the eventual extension of voting rights decades later, and then on through 20th-century milestones related to financial independence and jury service.

Libraries are scheduled to highlight this book alongside poetry, crafts and other programming for Women's History Month in March, giving local communities a chance to pair the book's narratives with live events.

Here’s the part that matters: recentering these stories can shift classroom emphasis and public programming, nudging readers and institutions to revise exhibit labels, lesson plans and commemoration choices.

- Founding-era evidence: a printed broadside of the Declaration that includes a woman's name as printer, signaling female participation in revolutionary publishing.

- July 4, 1876: suffragists interrupted centennial proceedings and read a separate declaration focused on women's rights.

- 1920: the eventual nationwide extension of voting rights to women, nearly half a century after the 1876 protest.

- Mid- to late 20th century: progress in financial autonomy and jury service that only became nationwide several decades after suffrage.

O'Donnell draws on portraits of individuals such as an influential sports star, the nation's first female cabinet member, and trailblazers who broke legal and political barriers—while also noting instances where women were passed over for leadership and then redirected into consequential roles in state and federal government.

Key takeaways:

- The book reframes textbook timelines by placing lesser-known women's acts next to famous moments.

- Local institutions planning Women's History Month can use these stories to broaden programming beyond the usual figures.

- Readers may find their own assumptions challenged, prompting reconsideration of who belongs in civic memory.

- Evidence in printed records and landmark protests creates clear entry points for renewed curriculum and exhibit design.

The real test now is whether classrooms and community programs treat these episodes as footnotes or as prompts for revision. The book's arrival amid library-centered Women's History Month activity creates a timely pathway for that discussion.

It’s easy to overlook, but the examples assembled here suggest that a handful of specific acts—printing, protesting, legislating—can be repurposed as teaching moments that alter public understanding without changing basic chronology.