Ice Immigration fight reaches Maryland as governor signs ban on 287(g) partnerships

Maryland Gov. Wes Moore signed a law on Feb. 17, 2026, that bars local sheriffs and police from partnering with U. S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement through the 287(g) program — a move supporters said pushes back on what they call a broader federal ice immigration campaign. The bill passed both chambers in January and was enacted amid chants of "Si se puede!" at the Annapolis ceremony.

Ice Immigration and Maryland’s new law

The law prohibits Maryland law enforcement agencies from entering 287(g) agreements that deputize local officers to act on ICE’s behalf, including detaining people in jails past their release dates for transfer to ICE custody. At the signing in Annapolis on Feb. 17, 2026, Moore was joined by Secretary of State Susan Lee, Lt. Gov. Aruna Miller, House Speaker Peña-Melnyk and Senate President Bill Ferguson.

Supporters who had pressed the legislature in 2025 celebrated the change. Jordy Diaz, an immigrant-rights advocate who had been disappointed when a 2025 ban failed, said the bill "alleviates some concerns" for people with family members vulnerable to deportation. The law requires nine existing sheriff’s office agreements in Maryland to be terminated immediately.

How the 287(g) program expanded and where others have pushed back

The 287(g) program was used at relatively low levels under prior administrations but has grown sharply. The context notes that about 130 agencies had 287(g) contracts in January 2025; that figure rose to more than 1, 300 by the time Maryland’s law was signed. Maryland had nine active agreements when the bill took effect, all held by sheriff’s offices.

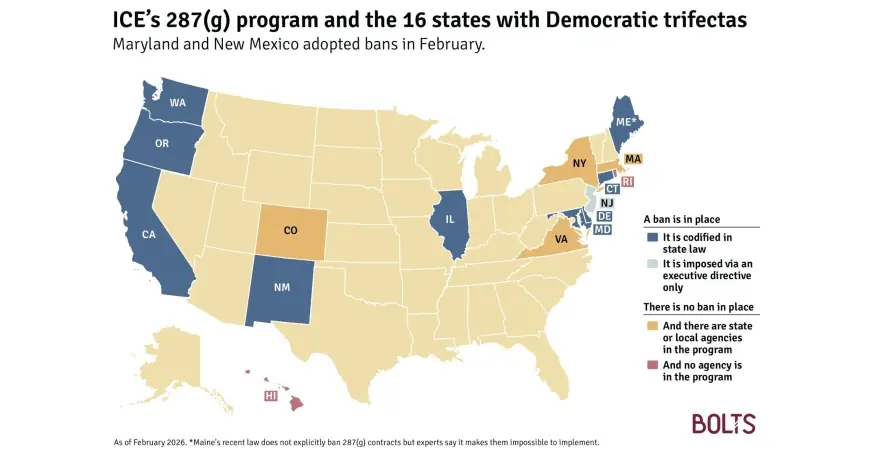

Maryland’s law follows a similar adoption this month in New Mexico and a January law in Maine that also bar local and state agencies from joining the program. Six other states—California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Oregon and Washington—already have laws banning 287(g) partnerships. New Jersey maintains a ban through an executive directive, though an effort to codify that ban into law was vetoed by the state’s outgoing governor in January.

Local consequences and political stakes

The reform immediately affects sheriffs who have been long-time 287(g) participants. One is Republican Chuck Jenkins of Frederick County, identified in the context as a longtime participant with ties to far-right networks; Jenkins is up for re-election this year, as are every county sheriff office in Maryland. The mandate to terminate agreements removes a legal pathway for ICE to access jails in the state, ending the local deputization that allowed federal agents to intercept people in custody.

The passage closed a chapter that many immigrant-rights advocates said opened more widely after the Trump administration returned to office. Advocates who had been disappointed by the legislature’s failure to act in 2025 framed the January vote and the Feb. 17 signing as correction of that earlier setback.

Four states that are under full Democratic control—Colorado, Massachusetts, New York and Virginia—still have local or state agencies that have joined the 287(g) program, and there is active legislation in at least three of those states aimed at changing that status.

The immediate practical effect in Maryland is clear: nine sheriff’s office agreements must end, limiting local law enforcement’s role in detaining people for transfer to ICE. The next political milestone noted in the context is the upcoming elections for county sheriff offices in Maryland this year, when officials such as Frederick County’s Chuck Jenkins will face voters.