UK goes experimental: look mum no computer eurovision song choice signals bold bid for Vienna

The United Kingdom has selected electronic artist and inventor Look Mum No Computer as its entry for the Eurovision Song Contest in Vienna. The announcement marks a clear shift toward experimental, tech‑forward performance as the nation prepares for the contest's final in May 2026 (ET).

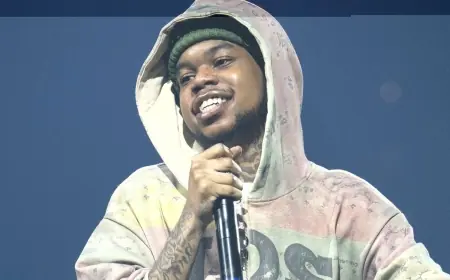

Artist background and the machines behind the music

Look Mum No Computer is the performance alias of Sam Battle, a musician who moved from indie rock frontman to solo electronic artist and creator of unusual musical devices. Over more than a decade of public work he has built a reputation not just for songwriting but for inventing instruments: organs made from repurposed toys, synthesized bicycles, Game Boys wired into vintage organs, and even a flame‑throwing keyboard. He also holds a world record for building the largest drone synthesizer, a feat that underscores his taste for spectacle and technical showmanship.

Battle has framed his Eurovision invitation as the culmination of long‑running creative work. "I find it completely bonkers to be jumping on this wonderful and wild journey, " he said, and emphasised his fandom for the contest: "I have always been a massive Eurovision fan, and I love the magical joy it brings to millions of people every year, so getting to join that legacy and fly the flag for the UK is an absolute honour that I am taking very seriously. " His public output blends music, engineering and documentary‑style process work, giving fans a deep window into how his audio inventions are built and performed.

Why the selection turns up the dial on experimentation

The pick signals a strategic gamble: rather than reverting to nostalgic or mainstream pop formulas that have produced mixed results in recent contests, the selection panel opted for an act whose strengths are originality and theatricality. The UK has struggled for consistent top‑ten placings in recent cycles, and selectors appear to be prioritising an entry that will stand out on a crowded stage.

That calculus is straightforward. Eurovision’s contemporary field rewards memorable visuals, distinctive sonic identities and acts that generate online conversation. An act who builds organs from toys and programs vintage electronics to produce pipe‑organ tones is unlikely to blend into the background. As Battle put it, he will be "bringing every ounce of my creativity to my performances, " and he teased, "I hope Eurovision is ready to get synthesized!"

What to expect in Vienna and the road ahead

No song title has been revealed yet, and the exact staging remains under wraps. But the artist’s track record suggests a performance that will combine custom instruments, engineered audio textures and a strong visual concept. The national selection process involved industry experts advising the broadcaster, and the choice of an inventor‑performer points toward a show designed for impact in a single, high‑stakes live moment.

Battle’s large online following and museum‑style collection of obsolete musical technology give him an immediate fanbase but also raise practical questions about translating studio creativity to a three‑minute televised performance judged by millions. Still, the acceptance of risk may be part of the plan: with Eurovision evolving into a playground for eccentric, genre‑bending acts, a daring presentation could win points for originality even if it divides opinion.

Fans and bookmakers will begin dissecting previews as soon as the song is released, and national rehearsals in Vienna ahead of the May 2026 final (ET) will provide the first real indications of how far the UK is willing to push theatrics and sonic experimentation on the Eurovision stage.