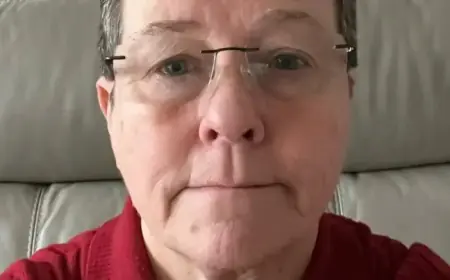

‘A Hymn to Life’ Review: Gisèle Pelicot’s Memoir Is a Powerfully Written Feminist Manifesto

Gisèle Pelicot’s new memoir, A Hymn to Life, turns a private catastrophe into a public challenge. Written with a collaborator, the book traces how Pelicot’s decades of domestic life unraveled when she discovered that her husband had been systematically drugging and allowing other men to rape her — and meticulously recording the assaults. The narrative is spare, direct and unflinching, and it doubles as a call to reassign shame from survivors to their abusers and enablers.

A personal reckoning laid bare

Pelicot, now in her seventies, recounts the moment she first learned the truth about her husband’s behavior: an investigation that began with clandestine photos taken under shoppers’ skirts spiraled into a revelation of a far more horrific pattern. Facing images of herself she did not recognize, she gradually came to understand that she had been drugged and assaulted repeatedly over many years. The memoir records both the factual unraveling — the discovery of labeled files, the police interviews, the courtroom ordeal — and the interior shock of a life rearranged.

The book does not shy away from harrowing detail. It describes how her husband mixed sedatives into food, including a scene in which lorazepam was slipped into mashed potatoes. Those details are precise and matter-of-fact, which makes them all the more devastating: Pelicot’s calm voice amplifies the horror rather than dulling it. She writes not only about the assaults themselves but about the slow, grinding process of naming what happened. That process extended to telling her three grown children, a moment she describes as the hardest she has ever faced.

From private horror to public reckoning

The legal fallout was extensive. Her husband was convicted on multiple charges, including rapes and attempted rape, and received a lengthy prison sentence. The trial drew national attention and laid bare a network of complicity: men who participated, a neighbor whose involvement was alleged, and a culture that left victims carrying the burden of shame. In court, Pelicot confronted people who tried to vilify her; in the memoir she condemns them in stark terms, calling them “parrots, deplorable mouthpieces, violent, cowardly little people” and insisting that shame belongs to perpetrators rather than to the woman who survived their crimes.

Pelicot’s decision to waive anonymity and speak publicly is central to the book’s force. She describes arriving each day at the courthouse accompanied by a protective phalanx of supporters, a visible counterweight to the isolation survivors often endure. The memoir maps how that public presence — protesters, police officers ensuring her safety, and the relentless attention of a nation — shaped her recovery as much as any private therapy or family conversations did.

Resilience, grief and the work of witnessing

Temperamentally, the book resists easy categorization as only a trauma narrative. Interspersed with courtroom scenes are scenes of modest domesticity: walks with her bulldog along the coast, long hikes through forests and dunes, the solace she finds in nature’s elements. Those passages serve as a counterpoint to the violence, underscoring a determined return to life. At the same time, Pelicot refuses to romanticize healing — she records complicated family responses, including the way her children grappled with their father’s deeds and her daughter’s own accusations.

Ultimately, A Hymn to Life reads as both testimony and manifesto. Pelicot insists on a reallocation of moral responsibility, demanding that society stop asking why victims don’t speak sooner and start asking how networks of predator and enabler operate with impunity. The memoir’s power lies in its refusal to be merely personal: by telling one woman’s story in unflinching terms, Pelicot forces readers to confront the broader structures that enable sexual violence and silence survivors.

Readable, controlled and bracing in its moral clarity, the book is a reminder that narrative can be an instrument of justice. Pelicot’s life after the trial — including a late-life relationship and continued search for answers — is neither tidy nor triumphant in the sentimental sense. It is, instead, a testament to survival and a stubborn insistence that shame must change sides.