New study reveals surprising sea life colonising the Titanic wreck 3,800 metres down

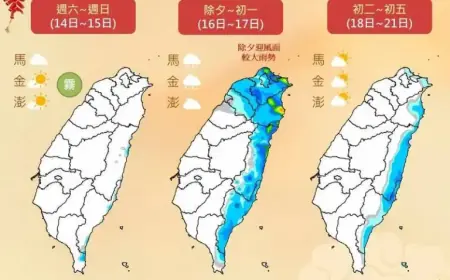

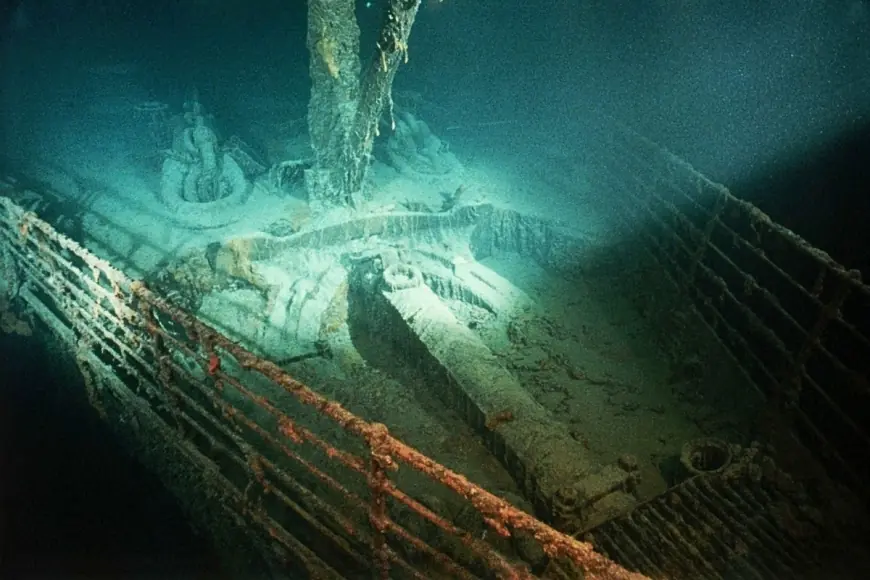

More than a century after the ship went down in the early hours of April 15, 1912 ET, the wreck of the Titanic has become a focal point not only for history but for deep-sea biology. A recent analysis of video footage from a 2022 submersible expedition reveals a thriving assemblage of animals living on and around the wreck at about 3, 800 metres depth.

Life on the iron: who moved in

Footage captured by manned and remotely operated vehicles shows a variety of megafauna clustering on the ship’s bow and nearby seabed. Observers identified ghost-white squat lobsters, a range of brittle stars and basket stars, sea pens, and sea anemones, alongside sea sponges and barnacles. One of the most visually striking finds was the presence of large-eyed rattail fish—pale-scaled deep-sea fish adapted to the dark, high-pressure environment.

Squat lobsters, despite their name, are not true lobsters; these flattened crustaceans are more closely related to hermit crabs and often appear in high densities where hard substrate is available. The wreck’s metal structure provides a rare hard surface in an otherwise soft-sediment environment, attracting organisms that need attachment points for feeding or shelter. Cold-water corals—described as twisted bamboo corals in the study—were also noted growing on parts of the wreck, adding to the site’s structural complexity and ecological niches.

Wreck versus ridge: a natural comparison

To understand how artificial structures influence deep-sea communities, researchers compared footage from the Titanic site with imagery taken at a nearby natural feature: a 2, 900-metre-deep seamount ridge roughly 40 kilometres southeast of the wreck. Prior to 2022 the ridge had not been explored, offering a fresh baseline for comparison.

Analysis across more than 1, 000 video frames showed that megafaunal organisms were present in virtually every image, whether at the wreck or on the ridge. While some taxa—such as certain brittle stars and sea pens—were common to both locations, the wreck appeared to concentrate species that favour hard substrate and crevices. The distribution suggests the ship acts as an artificial reef, modifying local biodiversity by supplying habitat features otherwise scarce on the abyssal plain.

Why these findings matter

Beyond the scientific curiosity of discovering life on a famous wreck, the observations carry practical implications for how underwater cultural heritage is managed. The Titanic has been visited by more than 20 expeditions since its position on the seabed became public in 1985, and the site continues to deteriorate as metal corrodes and sections crumble. Knowing which species rely on the wreck’s structure helps shape decisions about access, artifact recovery, and protection measures.

Researchers note that long-term monitoring of both the wreck and nearby natural habitats will be important for tracking ecological change over time. Insights gleaned from the Titanic serve as a case study in how artificial objects influence deep-sea ecosystems—information that could inform stewardship of other submerged cultural sites and guide policy on deep-ocean activity.

As exploration technologies improve, future missions are expected to provide higher-resolution imagery and broader spatial coverage, filling remaining gaps in knowledge about life at abyssal depths and the evolving relationship between human artifacts and the sea floor.