Tropical Cyclone Mitchell 21U: WA weather threat shifts from destructive winds near Karratha to flooding risk inland as the system weakens

Tropical Cyclone Mitchell, also known as Tropical Low 21U, has delivered a fast-moving burst of severe weather across Western Australia’s northwest and central west, with impacts stretching from the Pilbara down toward the Gascoyne and North West Cape. After intensifying offshore earlier in the event, Cyclone Mitchell has now weakened as it moved closer to the coast and then inland, changing the main hazard from extreme wind to heavy rainfall, dangerous surf, and flash flooding.

As of Wednesday, February 11, 2026 ET, the system is being treated as a weakening tropical cyclone or ex-tropical cyclone depending on its position and structure, but it remains capable of producing damaging gusts in squalls and locally intense rainbands well away from the center.

What happened: Cyclone Mitchell tracks past the Pilbara and targets the Karratha to Exmouth corridor

Cyclone Mitchell formed from Tropical Low 21U over warm waters off WA’s northwest and was named as it consolidated into a tropical cyclone. The early track kept the system near the Pilbara coastline, putting communities and industrial assets on alert from around Port Hedland through Karratha and Onslow, and later down toward Exmouth, Coral Bay, and the North West Cape.

For the Karratha region, the most disruptive period typically comes when the circulation passes close enough to funnel the strongest winds and heaviest squalls across the coast. Even if the eye stays offshore, the “core” and outer rainbands can deliver destructive gusts, short-notice power outages, and conditions that make it too dangerous to be on the roads.

Exmouth and the Ningaloo coast have faced a different mix of threats: wind-driven surf, coastal erosion, and the kind of heavy bursts of rain that can quickly overwhelm drainage in small towns and along highways. When a cyclone weakens near landfall, it can still produce intense rainfall because the moisture supply remains deep and the atmosphere stays unstable.

Cyclone WA: Why the risk profile changes after landfall

A cyclone’s headline category is mostly a wind metric. Once a system crosses the coast and begins to weaken, the wind field often contracts and the peak gusts ease, but the rainfall risk can increase as the decaying circulation drags tropical moisture inland.

That is the key shift with Cyclone Mitchell now: the most dangerous wind core is no longer the only story. Inland communities and road corridors can face flooding and washouts, sometimes after the strongest winds have passed. For travelers, that can be counterintuitive and leads to the most common mistake after a cyclone warning: assuming the threat is over because the wind has dropped.

Karratha cyclone disruptions: roads, ports, and essential services in the firing line

Cyclone responses in the Pilbara and Gascoyne are as much about infrastructure as they are about weather. When warnings rise, you typically see a cascade of operational decisions: ports clearing anchorages, resource operations reducing headcount, schools and services adjusting schedules, and emergency managers urging residents to shelter rather than drive.

That matters because Karratha, Dampier, and nearby industrial hubs are tightly connected to port operations and road links. Even short closures can create knock-on effects for freight, fuel supply chains, and fly-in-fly-out movement. The second-order impact is that a cyclone can disrupt normal operations for days after the wind peak, simply because roads need inspection, debris must be cleared, and power crews have to work through hazardous conditions.

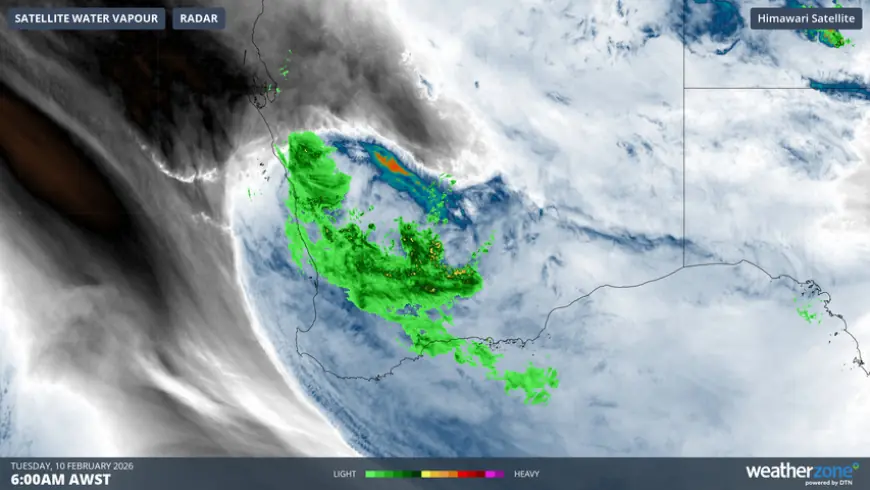

Weather radar and what it is showing: bands, not just the center

Weather radar snapshots during Cyclone Mitchell have been dominated by sweeping rainbands and embedded squalls, a reminder that the heaviest rain does not always sit neatly at the center. In weakening systems, the most intense cells can flare on the edges where the circulation interacts with land, sea-breeze boundaries, and uneven terrain.

For residents watching radar, the practical takeaway is timing: the worst conditions often arrive in bursts. A lull can be followed by a sudden return of torrential rain and gale-force gusts, especially overnight and around the hours when bands pivot across the same area repeatedly.

Exmouth cyclone and North West Cape outlook: surf, squalls, and lingering rain

For Exmouth, Coral Bay, and coastal communities near the North West Cape, the near-term concern remains squally showers, dangerous marine conditions, and the potential for localized flooding. Even after the center moves away, onshore winds and residual swell can keep beaches and coastal roads hazardous.

If you are in the warning area, the safest posture remains the same: stay off the roads during squalls, avoid coastal lookouts and surge-prone areas, and treat floodwater as a hard no. It only takes a small amount of moving water to push a vehicle off a road, and washouts can be invisible at night.

Behind the headline: why this cyclone is a stress test for preparedness and messaging

Context is everything. Cyclone Mitchell’s evolution from Tropical Low 21U into a named cyclone, then into a weakening inland-moving system, is a classic pattern that challenges public understanding. People anchor on the category number, but the real risk is often the combination of hazards, especially rainfall after landfall.

The incentives are clear. Emergency services want people to shelter early and not gamble on last-minute travel. Industrial operators prioritize protecting staff and securing critical assets. Local governments need road status clarity to prevent drivers from becoming rescue calls. Meanwhile, the public wants certainty, but cyclone forecasting is inherently probabilistic: small track shifts can decide whether Karratha gets the core winds or mostly rainbands.

What we still do not know

Several details remain fluid as the system evolves:

-

Exactly where the heaviest multi-hour rainfall totals will set up inland

-

How quickly winds will ease along the coast versus in squalls behind the center

-

Which road corridors will reopen first, and where washouts may persist

-

Whether the circulation re-intensifies briefly offshore or fully decays inland

What happens next: 5 realistic scenarios with triggers

-

Rapid weakening inland with a short-lived wind threat and a longer flood risk. Trigger: the center loses structure over land while rainbands persist.

-

A slower decay that keeps damaging gusts going in squalls along the coast. Trigger: the circulation hugs the coastline longer than expected.

-

Significant inland flooding and road closures expanding after the wind peak. Trigger: repeated rainbands training over the same catchments.

-

Coastal hazards linger even as skies clear inland. Trigger: residual swell and onshore flow.

-

Recovery accelerates if rain totals are patchy rather than widespread. Trigger: bands fragment and move through quickly.

Cyclone Mitchell is no longer just a “wind story” for WA. For Karratha, Exmouth, and surrounding regions, the next phase is about rainfall, flooding, road access, and the slow, practical work of restoring normal life after a major tropical weather hit.