Lucy Letby and “digitally anonymised”: what the label means and why it’s used

A fresh wave of public attention around Lucy Letby has brought an unfamiliar on-screen label into the spotlight: “digitally anonymised.” Viewers have seen it attached to interview participants in a recent true-crime documentary about the case, prompting a basic but important question—what does that phrase actually mean, and how is it different from ordinary anonymity?

Letby remains convicted of murdering seven babies and attempting to murder others at the Countess of Chester Hospital, and she is serving multiple whole-life sentences. Separate proceedings linked to the case have continued, including inquests that have been opened and then adjourned while a public inquiry process develops.

Who Lucy Letby is, and why the term is appearing now

Letby is a former neonatal nurse in England who was convicted in 2023 for multiple infant murders and attempted murders. The case has been re-examined in recent weeks through newly released long-form coverage and renewed debate among some medical and legal observers. That coverage includes interviews with people close to the events—parents, clinicians, investigators, and experts—some of whom may face privacy, safety, or legal constraints if identified.

That’s where “digitally anonymised” comes in: it’s a disclosure that someone’s identity has been concealed using digital methods more extensive than a simple blur.

What “digitally anonymised” means in a music-video-simple definition

In plain terms, “digitally anonymised” means the production has altered audio and/or video so the person cannot be recognized—not just by name, but by face, voice, and other identifying features.

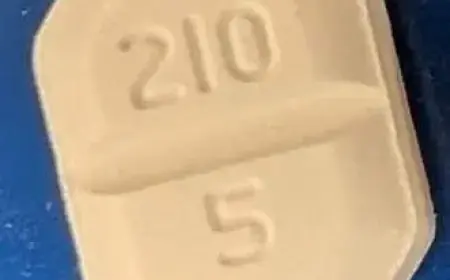

Common approaches include:

-

Face concealment (blur, pixelation, masking, or replacing facial features)

-

Voice alteration (pitch shifting, synthetic dubbing, or reconstruction)

-

Body/appearance changes (silhouette, altered posture or proportions, wardrobe changes)

-

Full synthetic representation (a digitally generated face or full “stand-in” mapped to the original performance)

The key point: “digitally anonymised” is a broad umbrella. It can mean anything from mild masking to a fully synthetic on-screen human designed to carry the interview while hiding the real person.

Why producers use it in high-profile criminal cases

There are several practical reasons an interviewee might not want to be directly identifiable:

-

Safety concerns (harassment, doxxing, threats, unwanted attention)

-

Legal limits (privacy protections, reporting restrictions, confidentiality obligations)

-

Workplace consequences (employment, professional registration, reputational risk)

-

Family protection (shielding children or relatives from identification)

In cases involving infant deaths and ongoing public processes, anonymity can also reduce the risk of retraumatizing families who never sought public visibility.

How it differs from “anonymised” in a legal/data sense

In everyday conversation, “anonymous” can simply mean “your name isn’t shown.” In privacy law and data protection practice, true anonymisation is higher bar: the information is transformed so the likelihood of identifying a person is remote, even when combined with other available details.

That distinction matters because a person can still be identifiable without a name—through a combination of:

-

specific job role and timing,

-

unique personal history,

-

location clues,

-

distinctive voice or mannerisms,

-

easily searchable contextual details.

“Digitally anonymised” is usually a production-side promise: “we’ve edited the presentation.” It doesn’t necessarily guarantee that re-identification is impossible, especially if the surrounding context is very specific.

What viewers should keep in mind when they see the label

“Digitally anonymised” also signals that what you’re seeing is not a raw, untouched interview image, and that can matter for trust and interpretation. The words spoken may be authentic, but the representation may be partially reconstructed to protect identity.

A useful mental checklist:

-

The person’s story may be genuine, but the visual/voice cues may be modified.

-

The more context the program gives (dates, wards, roles), the harder anonymity becomes.

-

If the technique involves a fully synthetic face or voice, it can feel more “real” than a blur—while still being an edited depiction.

What happens next in the Letby case orbit

The criminal convictions remain in place. Alongside that, related processes—such as inquests into some of the deaths and a broader public inquiry—continue to shape what can be said publicly and when. Those timelines are also one reason media projects may lean on heavier anonymisation methods: they’re built for global audiences while navigating local legal and personal sensitivities.

Sources consulted: The Guardian; Sky News; Information Commissioner’s Office (UK); UK Parliament (Justice Committee) report on open justice and reporting.