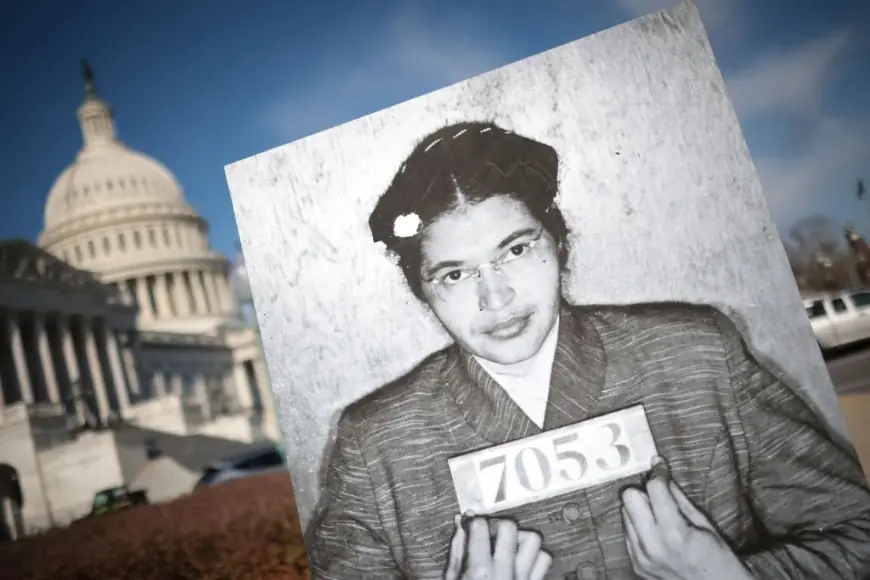

Rosa Parks: The Quiet Act of Defiance That Ignited a Movement, and Why Her Story Still Gets Misunderstood

Rosa Parks is often reduced to a single sentence: a tired seamstress who refused to give up her seat. That version is memorable, but incomplete. What happened in Montgomery, Alabama, on Thursday, December 1, 1955, was not an accident of exhaustion. It was a deliberate act by a seasoned civil rights organizer, set inside a segregated system designed to enforce hierarchy through daily humiliation. The reason her story still matters is not only moral. It shows how ordinary routines can be turned into leverage, and how movements succeed when personal courage meets collective strategy.

What happened: Rosa Parks’ arrest and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

On December 1, 1955, Parks refused to surrender her seat to a white passenger on a city bus in Montgomery. She was arrested and charged under local segregation rules. Her arrest became the catalyst for the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a mass protest in which Black residents refused to ride the buses for more than a year.

The boycott was not a spontaneous one-day reaction. It required coordination: meeting spaces, fundraising, carpools, communication networks, and leaders willing to negotiate and endure retaliation. The protest elevated the visibility of local organizers and helped bring a young pastor, Martin Luther King Jr., into national prominence. Eventually, federal courts ruled that segregated bus seating violated the US Constitution, and Montgomery’s buses were desegregated.

Behind the headline: context, incentives, and why this moment worked

Segregated transit was more than inconvenient. It was a daily theater of control. Bus drivers had authority that extended beyond customer service into policing: deciding where people could sit, when they could board, and how they could be treated. The system relied on normalizing compliance.

So why did Parks’ refusal become a turning point, when many others had also resisted in various ways?

Context mattered. Montgomery’s Black community had deep organizing capacity built through churches, civic groups, and civil rights networks. Parks herself was not politically new to the struggle; she had longstanding ties to local activism and had been involved in civil rights work well before 1955. That meant her case could be framed clearly and defended effectively.

Incentives mattered, too. Transit segregation created an economic pressure point. Black riders made up a large share of bus revenue, which gave the boycott real financial force. The city had an incentive to break the boycott, but also an incentive to restore stability. That tension created negotiating room.

Stakeholders were sharply aligned:

-

Black riders had the most immediate stake: dignity, safety, and equal access.

-

City officials and the transit system had economic and political stakes: revenue, order, and the maintenance of segregation.

-

Local civil rights leaders had strategic stakes: finding a case and a moment that could unify people and survive legal scrutiny.

-

White segregationists had reputational and political stakes: preventing a precedent that could unravel Jim Crow across the region.

Parks’ arrest became the match because it was legible, defensible, and galvanizing, and because the community had the organizational muscle to sustain action long after headlines would normally fade.

What people still get wrong about Rosa Parks

A few persistent myths distort what her legacy teaches.

Myth one: she acted only because she was physically tired. In reality, her decision reflected moral resolve and political clarity. The tiredness that mattered most was fatigue with indignity.

Myth two: one person changed everything alone. Parks was indispensable, but the boycott succeeded because thousands of people made costly, coordinated choices every day.

Myth three: the victory was immediate. It was not. The struggle took time, faced intimidation, and required legal persistence.

These misconceptions are not harmless. They shrink a collective movement into a feel-good anecdote and hide the practical mechanics of social change.

What we still don’t know and what history leaves messy

Even in well-documented events, some pieces remain contested or simplified:

-

How leaders weighed different legal and strategic options before rallying around Parks’ case

-

How internal debates shaped boycott tactics, messaging, and negotiations

-

How much unrecorded intimidation influenced private decision-making among participants

History often preserves speeches and court outcomes better than the daily fear, logistical strain, and trade-offs that movements endure.

Second-order effects: how one local protest reshaped national politics

The Montgomery Bus Boycott helped establish a blueprint: combine disciplined nonviolent protest, broad-based community participation, and legal strategy. It influenced later campaigns across the South, altered national media attention, and increased pressure on federal institutions to confront segregation. It also hardened resistance, intensifying backlash politics that would shape elections, policing, and public school conflicts for years.

What happens next: realistic lessons and triggers for modern movements

Rosa Parks’ story points to repeatable dynamics rather than a one-time miracle. Here are realistic takeaways that still apply:

-

Movements gain power when they target a system’s dependency, like revenue, legitimacy, or labor.

-

Endurance beats virality. The boycott’s length was the point.

-

Credible leadership and distributed participation matter more than any single hero.

-

Legal wins often follow sustained public pressure, not the other way around.

Rosa Parks is remembered for refusing to move. Her deeper legacy is that her refusal helped millions decide to move together.