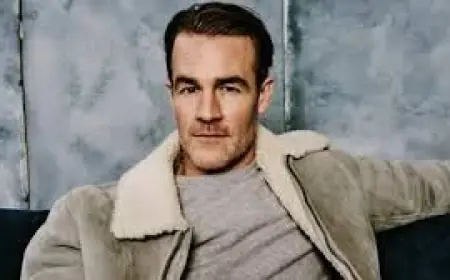

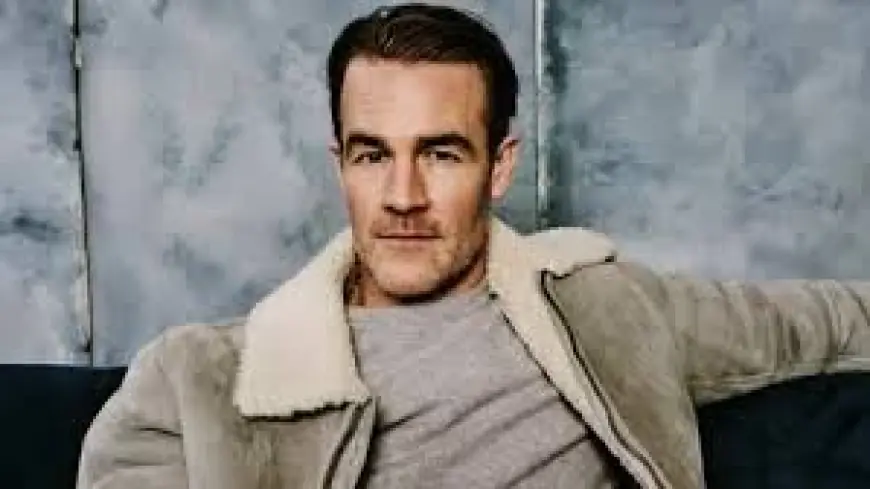

Why James Van Der Beek Needed Help Covering Massive Medical Bills

James Van Der Beek, the actor best known for the title role in Dawson's Creek, died on Wednesday, Feb. 11, 2026 (ET) at age 48 after a three-year fight with colorectal cancer. In the months before his death his family made a public appeal for help paying medical bills, a move that highlighted how even recognizable names in entertainment can face crippling healthcare costs.

Medical costs, auctions and a public plea

Van Der Beek's wife made an urgent public request for donations to prevent the family from losing their home. The campaign raised roughly $2. 3 million to help cover mounting expenses tied to his care. In addition to the fundraiser, the actor himself put decades of memorabilia up for auction to help bridge the gap: a tartan shirt from the pilot of his breakout series, a necklace once used on the show, and sneakers from his role in Varsity Blues were among the items he said he had been storing for years and was now selling to help pay bills.

Those efforts underscored a stark reality: costly cancer treatments, long-term care needs and related expenses can rapidly drain savings. For a household with six children, the combined pressures of medical outlays and daily family costs made the fundraising a final lifeline.

Why fame didn’t translate to financial security

Part of the financial squeeze stemmed from the way Van Der Beek was paid early in his career. He has been candid about his original contract for Dawson's Creek, saying it offered little money and lacked residuals — the repeat-payments performers receive when shows are rebroadcast or streamed. He remarked that he was 20 at the time and that it was a bad contract that left him with almost nothing from the series' later success.

Residuals have been a key income stream for many performers from earlier TV eras, sometimes amounting to millions annually for popular shows. Changes in how shows are distributed, particularly with the rise of streaming, have shrunk or altered those revenue channels, making predictable long-term income less reliable for many working actors.

Union health benefits are another piece of the puzzle. To qualify for health coverage through the primary performers' union, members typically must work a set number of days on union shoots in a year or meet a modest earnings threshold on union work. Those rules — such as a 108-day work requirement or a minimum earnings level on union projects — can leave performers without benefits during stretches of limited hiring. It remains unclear whether Van Der Beek's later work met those thresholds; he continued to take roles after his diagnosis, including appearances in 2025, but episodic work alone may not guarantee ongoing coverage.

Broader implications for actors and the uninsured

Van Der Beek's situation is not unique. Other notable performers have spoken about gaps in coverage when health crises hit, and some have also relied on friends, fans and public appeals to manage medical costs. Colleagues in the industry point to shrinking residuals and changing business models as factors that have eroded a once-more-stable financial cushion for many mid-level and veteran actors.

One working actor noted that revenue streams performers depended on have largely disappeared, and that many survive by working when hired and struggling when they are not. The combination of fewer residuals, sporadic freelance employment and union eligibility thresholds can produce precarious circumstances — even for those who once enjoyed high visibility.

The outpouring of public support for Van Der Beek's family demonstrated how personal networks and fan communities can mobilize in a crisis. But it also prompted renewed questions about the safety nets available to performers and the millions of other Americans who face catastrophic medical bills without consistent employer-based insurance or sufficient savings.

As the entertainment industry continues to adapt to new distribution models, Van Der Beek’s struggle will likely remain part of a larger conversation about how creative professionals are compensated and how they secure health protections when illness strikes.