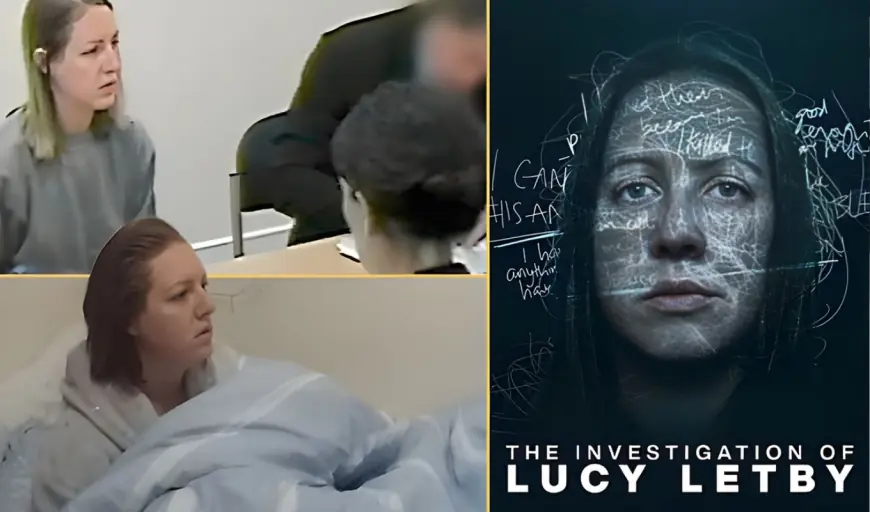

Lucy Letby documentary backlash focuses on “digitally anonymized” AI visuals; no confirmed changes announced yet by Netflix or producers

A new Lucy Letby documentary has sparked an unusually focused backlash: viewers aren’t arguing only about the case, but about the film’s use of “digitally anonymized” witness interviews that appear to replace faces with AI-like visuals. The choice was intended to protect identities while keeping interviews on camera, yet many true-crime fans say it pulls them out of the story, reads as uncanny, and feels poorly matched to testimony involving bereaved families.

As of Sunday, February 8, 2026 (ET), there are no confirmed changes to the documentary’s presentation announced publicly by the streaming platform or the producers, even as complaints continue to spread across social media and discussion forums.

What viewers mean by “digitally anonymized”

The technique goes beyond familiar anonymity tools like blurring, silhouettes, or filming from behind. In these interviews, the speaker’s face appears digitally replaced with a realistic, human-like overlay that moves with the person’s speech and expression. Voices may also be modified.

The result aims for a middle ground: keep the emotional immediacy of seeing someone speak while preventing viewers from identifying them. But that middle ground is exactly what’s dividing audiences—some experience it as protective, others as unsettling.

Why the AI masking is dividing true-crime audiences

True-crime documentaries lean heavily on credibility and emotional connection. When an interview looks “almost real” but not quite, some viewers feel the method competes with the content—especially in scenes describing infant deaths and the long aftermath for families.

The strongest critiques cluster around a few themes:

-

Uncanny-valley distraction: subtle facial movement artifacts can become the main thing viewers notice.

-

Emotional mismatch: grief filtered through synthetic visuals can feel dehumanizing, even if the words are authentic.

-

Trust concerns: once a face is altered, some viewers start questioning what else has been shaped, fairly or not.

-

Sensitivity to tone: the closer the documentary gets to real pain, the less tolerance some audiences have for visible production “tricks.”

Defenders argue the opposite: that conventional blurring can strip away humanity and that this method preserves expression while reducing doxxing and harassment risk for people connected to a notorious case.

The privacy-and-realism tradeoff

Anonymity is not an abstract concern here. The Letby case remains a lightning rod, and anyone perceived as a participant—witnesses, acquaintances, even family—can become a target for online scrutiny. Producers face a genuine dilemma: how to let people tell their stories without turning them into permanent, searchable faces.

Traditional options each carry costs. Heavy blur can make testimony feel distant. Off-camera audio may feel less engaging to some viewers. Actors reading statements can invite accusations of dramatization. The “digitally anonymized” approach attempts to keep the interview format intact while blunting identification.

The backlash suggests that for some viewers, the technique solves the safety problem but creates an authenticity problem: the audience is asked to sit with something presented as intimate and human, while the visuals signal something synthetic.

Why this controversy is hitting now

The argument is also landing at a moment when audiences are increasingly alert to AI in media—voice cloning, image alteration, and synthetic performance. That awareness changes how viewers interpret even well-intended choices. A blur reads as concealment. A realistic overlay can read as replacement.

In true crime, that distinction matters because the genre is already contested: viewers want factual rigor, victims’ dignity, and transparency about storytelling methods. When the visuals look manufactured, it can raise anxiety that the narrative itself is being “produced” rather than documented—even when the underlying material is real.

This is also the kind of debate that can spread quickly because it’s easy to demonstrate. A short clip of an interview face is enough for audiences to form an opinion, and the conversation becomes about the technique rather than the broader reporting.

Updated: No confirmed changes announced yet

Despite the scale of the online reaction, there has been no publicly confirmed announcement (as of February 8, 2026, ET) of edits, re-cuts, replacements, or removals of the “digitally anonymized” segments.

That doesn’t rule out future adjustments—streaming releases can be updated—but right now the controversy is operating in a familiar gap: viewers want an explanation or a change, while the people behind the documentary have not publicly signaled a shift.

In the near term, the most likely outcome is continued debate rather than immediate action. Longer term, the controversy may influence genre norms: clearer on-screen disclosure, tighter limits on synthetic masking, or a return to more traditional anonymity methods in cases involving high trauma.

Sources consulted: Netflix, The Guardian, The Times, ITV News