Epstein files released as DOJ posts millions of pages, reviving Mandelson questions

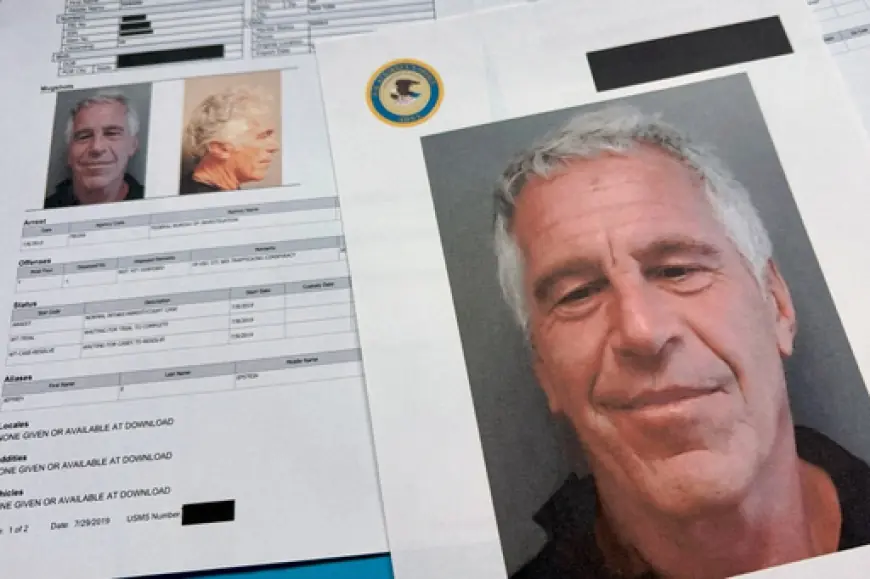

The epstein files expanded sharply Friday, Jan. 30, 2026, after the DOJ posted a massive new tranche of investigative material tied to Jeffrey Epstein and the prosecution of Ghislaine Maxwell. The US Department of Justice framed the drop as a major step toward meeting the disclosure requirements of the Epstein Files Transparency Act, even as the release arrived weeks after the law’s original deadline and featured extensive redactions.

The new publication is already reshaping political and legal debates on two fronts: in Washington, over what the government can lawfully disclose while protecting victims; and in London, where fresh attention has returned to Peter Mandelson after documents surfaced showing money transfers involving Mandelson’s husband and Epstein.

Epstein files: What the DOJ put out Friday

The newest batch is the largest public disclosure yet from federal Epstein-related files, and it comes with a clear emphasis on volume rather than narrative clarity. The department says the material spans investigations across years, pulling from devices, records, and case files connected to Epstein and Maxwell.

| What was published Jan. 30, 2026 (ET) | Amount |

|---|---|

| Pages added in the new release | 3+ million (described as about 3.5 million responsive pages overall) |

| Videos included | 2,000+ |

| Images included | ~180,000 |

| Total records reviewed as potentially responsive | 6+ million pages |

The department also characterized this release as the final planned cache under the transparency law, while acknowledging that some material remains blacked out or withheld under statutory exceptions.

Redactions, privacy, and what’s still missing

The central tension of the latest disclosure is the trade-off between openness and harm prevention. The department says it withheld or redacted information that could identify victims, disclose medical information, expose material depicting child sexual abuse, reveal privileged communications, or interfere with ongoing investigative work.

That approach has become the fault line in the public argument: transparency advocates want names and specifics; prosecutors and victim advocates warn that “full visibility” can quickly become forced exposure for survivors and witnesses. The government is trying to satisfy the statute while limiting re-victimization and avoiding legal problems that could jeopardize prosecutions or appeals.

The practical outcome for readers is that many files are difficult to interpret in isolation. Large sections are blacked out, names can be missing, and context can be fragmented across different formats (images, logs, interview notes, and attachments). The result is a record dump that will take time to map—especially for lawmakers, journalists, and attorneys trying to distinguish between verified investigative material and untested tips or claims.

Ghislaine Maxwell material and case context

The new release again centers Maxwell as the key connective figure in the federal record. Maxwell remains the only major Epstein associate convicted in federal court, serving a 20-year sentence while continuing to litigate her case. Her case materials intersect with the broader “files” story because they contain the most developed court-tested narrative of how Epstein’s recruitment and abuse network operated.

Friday’s disclosure includes Maxwell-related administrative and booking material and continues the pattern of shielding women’s identities broadly, leaving Maxwell as the exception because she is the convicted defendant. That choice underscores how the department is trying to avoid turning the release into a searchable directory of victims or alleged victims, while still disclosing a substantial portion of government holdings.

The department also emphasized that the public should not treat every mention of a name in the files as proof of wrongdoing. The records include interviews, tips, and investigative leads, and not all items are corroborated or tied to charges.

Peter Mandelson returns to the spotlight

One of the most politically sensitive revelations in the latest tranche involves Peter Mandelson, the British political figure whose relationship with Epstein has already been under scrutiny in the UK. Newly surfaced emails show Mandelson’s husband, Reinaldo Avila da Silva, requested financial help from Epstein in September 2009—shortly after Epstein’s release from custody in Florida—and received a £10,000 transfer. The documents also reflect additional payments in 2010, including recurring transfers and a separate $13,000 payment.

Those details are likely to intensify questions about judgment and proximity rather than criminal liability. The emails reinforce that Epstein maintained relationships and influence channels even after his 2008 conviction, and that people in his circle still sought financial assistance. Mandelson has previously faced political consequences connected to his Epstein ties; the renewed focus now is on whether financial links connected to his household deepen the optics and accountability debate.

What comes next for Congress and the DOJ

The immediate next step is oversight. The department has signaled a mechanism for Congress to seek access to less-redacted material under confidentiality conditions, alongside a promised accounting of what was withheld and why. That sets up a two-track process: the public portal as the “open record,” and lawmakers as the gatekeepers of more sensitive context.

Two risks now loom. First, selective interpretation: partisan actors may highlight sensational fragments while ignoring redactions and caveats, fueling misinformation. Second, privacy harm: even redacted files can be triangulated with outside data, a concern that grows as more images and logs circulate online.

For the justice system, the stakes are narrower but sharper: whether the disclosure process protects victims and preserves the integrity of ongoing matters while meeting the legal mandate to publish. For the public, the release is less a single reveal than a new phase—one where meaning will be assembled over weeks, not hours.

Sources consulted: U.S. Department of Justice; Reuters; Associated Press; Financial Times; ABC News; CBS News