Canada Fighter Jets and NORAD: A New F-35 Flashpoint Raises Big Questions About Sovereignty and Air Defense

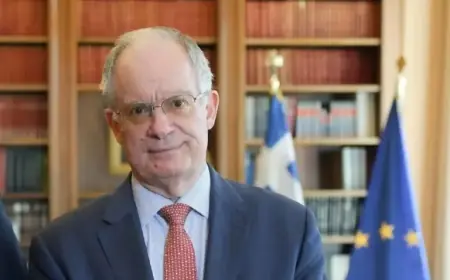

A fresh round of Canada news is putting Canada fighter jets and NORAD back at the center of a high-stakes conversation: who protects Canadian airspace, with what aircraft, and on whose terms. In comments circulating Tuesday, January 27, 2026, ET, the U.S. ambassador to Canada, Pete Hoekstra, suggested the United States could end up flying more of its own fighter jets in Canadian airspace if Canada backs away from its planned F-35 purchase. He also argued NORAD itself might need changes if Canada’s fighter capability falls short.

The immediate impact is political and symbolic, but the underlying issue is practical: North American air defense depends on both countries fielding credible, ready-to-fly fighters, especially as Arctic activity and long-range threats keep rising in strategic importance.

What happened in the latest Canada news on fighter jets Canada

Canada’s plan is to replace its aging CF-18 fleet with 88 F-35A fighters. The purchase remains under government review, and no final change or cancellation has been announced. That review, however, has created uncertainty about whether Canada will take the full fleet, stretch deliveries, or explore alternatives.

Hoekstra’s message, in plain terms: if Canada ends up with fewer jets or a longer gap, the U.S. would still need to meet shared continental defense requirements. That could mean more U.S. fighters operating in and around Canadian airspace under NORAD tasks, potentially more often than Canadians are accustomed to seeing.

Why NORAD is at the heart of the dispute

NORAD is built on a simple bargain: integrated early warning and integrated response. The U.S. and Canada already coordinate closely, and NORAD operations can involve cross-border activity when needed. But the political sensitivity spikes when the discussion shifts from routine coordination to the idea of the U.S. “filling in” inside Canada more frequently.

That distinction matters because NORAD is not only a military arrangement; it’s also a public signal of shared responsibility. If Canadians perceive a capability shortfall that forces a heavier U.S. hand, it can quickly become framed as a sovereignty issue, even if the operational mechanics remain legal and coordinated.

Behind the headline: incentives, pressure points, and who has leverage

This story isn’t just about aircraft performance. It’s about incentives and leverage:

-

Ottawa’s incentive: avoid a fighter gap while managing cost, schedule risk, and domestic politics. Fighter procurement is a multi-decade commitment that can crowd out other defense priorities.

-

Washington’s incentive: ensure the northern approach to the continent remains covered without taking on an open-ended burden. The U.S. also benefits from allied interoperability and predictable industrial planning.

-

Military incentive on both sides: keep training, mission planning, and classified systems aligned so forces can operate as one team during real-world intercepts or crises.

Stakeholders with the most to gain or lose include the Royal Canadian Air Force, Canadian taxpayers, communities tied to basing and maintenance work, Arctic and northern communities that rely on rapid response, and political leaders managing a wider relationship that now mixes defense, trade, and diplomacy.

Where Canada’s fighter jet timeline stands right now

Even with the broader review, the near-term schedule is becoming harder to ignore. Canada’s current plan anticipates the first F-35A arriving at Luke Air Force Base in 2026 for pilot training, with the first aircraft arriving in Canada in 2028 as domestic infrastructure and support systems come online. The program is also structured as a phased delivery over years, not a single handover.

That timeline creates a narrow window for decision-making. Delaying or shrinking the fleet doesn’t just change a purchase order; it can ripple into pilot training pipelines, base construction, maintenance staffing, weapons integration, and Canada’s ability to meet NORAD and allied commitments without overusing the CF-18s.

What we still don’t know

Several missing pieces will decide whether this is a short-lived political flare-up or a longer strategic reset:

-

Whether the Canadian review will recommend sticking with 88 jets, reducing the total, or stretching deliveries.

-

How Ottawa would manage the CF-18 fleet if the transition slows, including costs and readiness trade-offs.

-

Whether any NORAD-related operational changes would require formal renegotiation, new public guidance, or simply updated planning assumptions.

-

How much the debate is driven by procurement fundamentals versus wider bilateral tensions that spill into defense.

What happens next: realistic scenarios and triggers

-

Status quo, reaffirmed: Canada publicly recommits to the full F-35A plan and accelerates infrastructure work. Trigger: a review conclusion that prioritizes operational certainty over reopening competition.

-

Slowdown without reversal: Canada keeps the program but stretches deliveries or scopes near-term spending. Trigger: fiscal pressure or competing priorities in the federal budget.

-

Partial fleet, heavier NORAD reliance: Canada reduces total aircraft and leans more on coordination for coverage. Trigger: a political decision to cap long-term costs, paired with assurances that NORAD can manage risk.

-

Alternative exploration with limited change: Canada investigates substitutes but keeps the initial tranche moving to avoid a training gap. Trigger: desire for bargaining leverage without triggering a full restart.

-

Bilateral friction becomes the story: The fighter debate becomes a proxy fight about sovereignty and trade. Trigger: sharper rhetoric or policy moves that broaden the dispute beyond defense planners.

Why it matters

Canada fighter jets are not just procurement headlines; they are a readiness story with real-world consequences. NORAD intercepts are time-sensitive, and the Arctic is unforgiving: distance, weather, and sparse infrastructure punish delays. The more uncertainty around fighter availability, the more pressure shifts onto stopgap measures and the more politically charged normal NORAD cooperation can become.

For Canadians, the core question is simple: can Canada maintain credible, independent air-defense capacity while staying fully integrated with its closest military partner? The answer will be shaped as much by budgets and timelines as by aircraft themselves.