Idaho murders update: New crime-scene photo release reignites “Idaho 4” debate as Kaylee Goncalves’ family pushes back

New developments in the Idaho murders case are pulling the “Idaho 4” back into the spotlight in January 2026, even though Bryan Kohberger has already been sentenced. A fresh release of case photographs tied to the King Road crime scene has triggered a new wave of backlash from victims’ families, including the family of Kaylee Jade Goncalves, who say repeated public record drops risk turning the case into permanent online trauma.

The latest moment is less about courtroom drama and more about control: who gets to see investigative material, how fast it spreads, and whether families have any meaningful warning before it becomes public.

In recent days, two storylines have converged—newly surfaced images from the investigation, and a wrongful-death civil lawsuit filed by all four families that argues preventable failures contributed to the tragedy.

-

A new batch of investigation photos from the King Road case circulated publicly this week, renewing outrage over graphic material and privacy.

-

The Goncalves family is among those demanding tighter safeguards and better notice when sensitive records are released.

-

All four families filed a wrongful-death civil lawsuit earlier this month, shifting the case into a new phase beyond criminal sentencing.

-

The push-and-pull now centers on public records laws versus victim-family privacy in a case that remains intensely public.

-

The next pressure point is likely to be how courts and agencies manage future releases—redactions, timing, and access limits.

Idaho 4 crime-scene photos: what was released this week and why it matters

On Wednesday, January 21, 2026, a new set of case photographs connected to the King Road house became widely viewable through the same public-records ecosystem that has been releasing non-exempt investigative material since sentencing. The images include scenes from inside and outside the home and additional evidence photos related to the investigation.

For many following the Idaho murders, the reaction has been immediate and emotional—not because the criminal case lacks an ending, but because the digital afterlife of the evidence has no clear boundary. Once files hit the public sphere, they can be reposted endlessly, stripped of context, and used as content.

Families have been warning for months that this is the nightmare scenario: a tragedy packaged into clips and thumbnails. The renewed attention around this week’s release has intensified calls for a system that gives families more time and more protections before sensitive material becomes public.

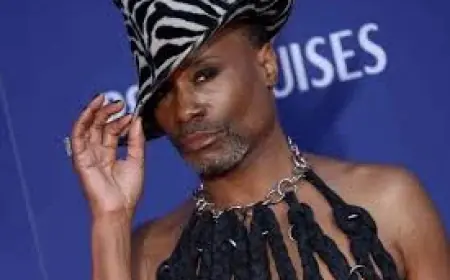

Kaylee Goncalves’ family: the core complaint is notice, dignity, and permanence

The Goncalves family has consistently framed the issue as dignity for Kaylee and the other victims. The concern is not abstract. Public releases can be re-traumatizing, especially when images spread without filters or warnings—and when relatives learn about them at the same time the wider internet does.

In this week’s backlash, a central point has been timing. Families argue that even when records are legally releasable, the process should include meaningful notice and safeguards that recognize the stakes for loved ones. That’s why each new drop is treated not as a routine “public file update,” but as a fresh wound.

This isn’t about hiding the facts of the case. It’s about limiting harm caused by the repeated circulation of the most sensitive parts of the record.

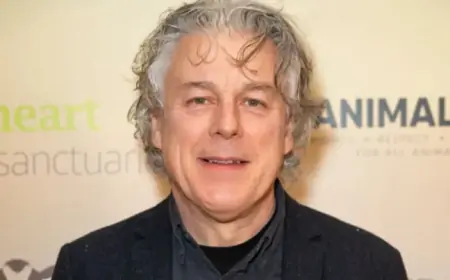

Lawsuit filed by all four families: the case moves into a new phase

Separate from the photo release, all four victims’ families filed a wrongful-death civil lawsuit earlier this month against Washington State University, where Kohberger was a graduate student and teaching assistant at the time of the killings. The civil complaint alleges the university failed to act on warning signs about Kohberger’s behavior and seeks damages.

This lawsuit matters because it broadens the accountability question. The criminal case ended with Kohberger’s guilty plea and a life sentence without parole, but civil litigation can reopen timelines, policies, and institutional decisions—often through discovery and depositions. It can also keep the story in the public eye far longer than families ever wanted, even as it becomes one of the few remaining routes to answers and accountability outside the criminal process.

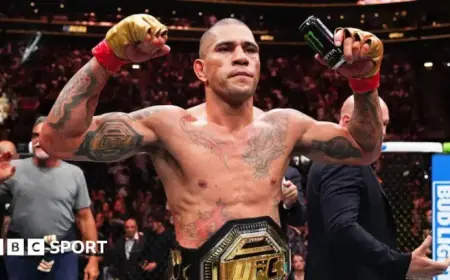

Why “Idaho murders” is trending again despite sentencing

Kohberger pleaded guilty in 2025 and was sentenced to four consecutive life terms without the possibility of parole. That should have closed the chapter. Instead, the story keeps resurfacing because evidence releases and civil actions keep generating new headlines—and because the case has become a test of how public-record transparency works when the “public interest” collides with personal devastation.

A short historical context helps explain the friction: in major American criminal cases, public-record releases often accelerate once trials end or sealing orders expire. In the internet era, that can shift a case from “justice system story” into “permanent content stream,” forcing agencies and courts to rethink how transparency can coexist with basic human dignity.

FAQ

Is there a new trial in the Idaho 4 case?

No. The criminal case concluded with a guilty plea and sentencing in 2025, but new public releases and civil litigation are driving fresh headlines.

Why is Kaylee Goncalves’ name trending again?

The renewed attention stems from newly circulating investigation photos and the family’s continued push to limit the harm caused by sensitive records becoming widely available.

What is the new lawsuit about?

All four families filed a wrongful-death lawsuit earlier this month against Washington State University, alleging preventable failures related to warning signs and institutional action.

The next likely flashpoint is whether future releases are slowed, more heavily redacted, or managed with stricter notice protocols for families. Even after a criminal sentence, the Idaho murders remain a live debate about how a community—and a legal system—protects victims’ dignity once evidence enters the public domain.