Kid Rock halftime show draws lip-sync debate in Super Bowl counterprogramming

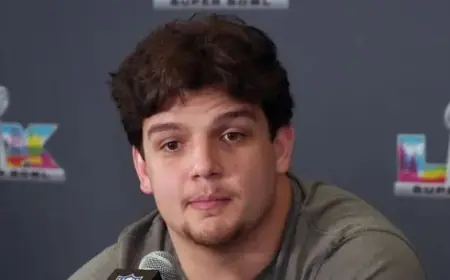

Kid Rock’s halftime performance has become a flashpoint in the post–Super Bowl conversation after viewers circulated clips that appeared to show his vocals out of sync with the music. The set was part of Turning Point USA’s “All-American Halftime Show,” an alternative program timed to run opposite the official Super Bowl LX halftime spectacle on Sunday, February 8, 2026.

Kid Rock has denied lip-syncing, saying the mismatch was a production syncing problem tied to how the show was recorded and edited, not a pre-recorded vocal track.

What the alternative halftime show was

Turning Point USA positioned its halftime event as a values-forward entertainment option for viewers who wanted a different feel from the main broadcast. The program was promoted as family-friendly and patriotic, and it leaned heavily into mainstream rock and country.

Kid Rock headlined the show and was joined by a small lineup of country artists. The event was recorded ahead of time and packaged to air during the Super Bowl’s halftime window, putting it in direct competition for attention during one of the most watched slices of TV each year.

Why lip-syncing rumors spread

The controversy stems from widely shared clips where Kid Rock’s mouth movements didn’t appear to match the audio cleanly during “Bawitdaba.” In the short, fast-cut segments that traveled online, the disconnect looked like the classic tell of a pre-recorded track.

That perception gained traction because the alternative show was not a traditional live-in-stadium broadcast. When performances are taped, viewers often assume the audio can be “fixed” in post-production—so visible syncing issues can read as suspicious, even when the underlying audio was actually recorded live on set.

Kid Rock’s response and the “syncing issue” claim

In a televised interview aired Monday and Tuesday, Kid Rock said he was performing in real time during the taping and that the problem came from syncing during editing. He described moving aggressively around the stage and said his DJ filled in portions of the vocal delivery, which can complicate mixing and alignment when the final cut is assembled.

His core point: if the vocals had been fully pre-recorded, the final sync would have been easy to perfect. Instead, he argued, the production team struggled to match the visual and audio tracks cleanly, leaving moments that looked “off” to viewers.

The numbers battle for attention

Even as the lip-sync debate drove memes and commentary, the alternative show posted sizable digital reach. Publicly cited metrics put its peak livestream audience at roughly 6.1 million viewers, with the archived performance later surpassing 21 million views on major video platforms.

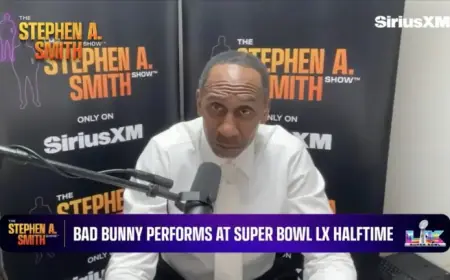

The official halftime show—headlined by Bad Bunny—has also generated big online engagement, with its official performance upload topping roughly 55 million views in the first days after the game. Those figures are not directly comparable to traditional TV ratings, but they provide a snapshot of what audiences rewatched and shared most.

What it means for halftime counterprogramming

The immediate takeaway is that halftime “counterprogramming” can pull meaningful attention when it gives a motivated audience a clear alternative. But it also comes with risks: taped presentations face a different credibility test than live stadium performances, and technical imperfections can become the story overnight.

For Kid Rock, the episode reinforces how fast post-game narratives can shift from music to mechanics—especially when short clips circulate without context. For organizers, it’s a reminder that production polish matters as much as messaging when an event is designed for rapid online replay.

What to watch next

-

Whether Turning Point USA releases additional behind-the-scenes material showing raw audio or rehearsal footage

-

Any updated performance metrics that distinguish livestream viewers from later replays

-

Whether other artists embrace (or avoid) future halftime counterprogramming amid the backlash-and-attention cycle

Sources consulted: Associated Press; Entertainment Weekly; People; ESPN