B.C. Ghost Town Owner Aims to Transform Kitsault into Energy Hub

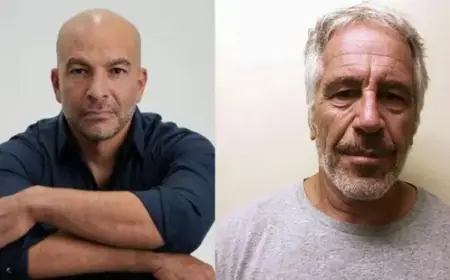

Kitsault, a once-thriving mining town in British Columbia, is poised for transformation. Krishnan Suthanthiran, its owner and a medical technology entrepreneur, aims to turn this ghost town into an energy hub. He has a vision of connecting Alberta to the coast with two pipelines: one for natural gas and one for crude oil.

Reviving Kitsault: A Blueprint for the Future

Located about 140 kilometers northeast of Prince Rupert, Kitsault has remained largely uninhabited since its mining days ended in the early 1980s. Originally established in 1981 for molybdenum mining, the town reached a peak population of 1,200. However, the closure of the mine left it a shell of its former self, with 92 houses and various public amenities left intact.

Historical Background

- 1981: Molybdenum mine opens, leading to a population boom.

- 1983: Mine closure results in an empty town.

- 2004: Kitsault is put on the market with preserved 1980s infrastructure.

Suthanthiran purchased Kitsault for approximately $7 million twenty years ago. His initial plans included projects like an eco-resort and a movie studio, none of which materialized. However, Suthanthiran is now optimistic about the town’s potential as a marine terminal for energy exports.

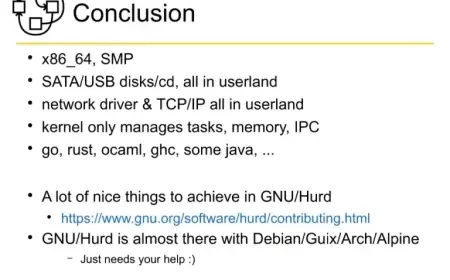

Proposed Energy Initiatives

Suthanthiran’s updated proposal focuses on transforming Kitsault into a center for energy exports. He has outlined ideas such as:

- Construction of a marine terminal on Observatory Inlet, aimed at exporting crude oil to Asian markets.

- Establishment of a facility to manufacture liquid butanol from natural gas, a versatile fuel alternative.

His plan leverages the town’s existing infrastructure, including housing and hydro services, making it attractive for rapid development. Suthanthiran believes this project will benefit both Canada and the First Nations, stating, “I truly believe that this is the right thing for Canada.”

The Path Forward

Political and economic shifts, particularly regarding U.S. energy policies, have heightened the urgency for Canada to diversify its energy exports. The Alberta government has committed $14 million for early work on a proposed oil sands pipeline, reinforcing the need for infrastructure in Canada’s energy sector.

Suthanthiran acknowledges the hesitation among Canadian industries to lead such projects. He remains open to selling Kitsault if it means advancing this vision, saying, “I don’t have to own the town forever.” With supportive local Indigenous partnerships likely to influence outcomes, Kitsault could become a pivotal player in Canada’s energy future.

Experts suggest that Kitsault possesses strategic advantages, such as navigable waters and existing utilities. As the geopolitical landscape evolves, the opportunity for Kitsault to emerge as a vital energy hub could finally be within reach.